Last week (ok, that’s not true, it’s more than two weeks ago, I dreaded writing this blog and procrastinated) I told you all about the slippery of the truth. Truth is not so true at all. Truth is a status we give to things that have seeped through a complex system of perceptions, heuristics and prejudices. Despite that system, truth is so important to us that go to war for it. With guns, on the highway or on social media.

What we also want to wage wars for, perhaps even more so than truth, is about righteousness. Moral considerations are absolute: stealing is bad, saving someone from drowning is good. Despite the tricks philosophers try to play with us (just look at the trolley problem), we never – or almost never – doubt our moral consideration. Righteousness… just is?

Unfortunately, righteousness faces the same problems as truth: we are just steering our elephant again. Our first instinctive reaction comes from our heuristics, our emotions, our instinct. For example, as an anti-authoritarian person, I have an instinctive positive reaction to actions that fight for a better climate. Even if my 13 year old son wants to play truancy and travel to The Hague with classmates to demonstrate, I automatically react positively. Only to find out too late that I really have a problem with the fact that my child is traveling alone in a full train to The Hague and demonstrating in a big crowd of people I don’t know. Not to mention the truancy…

The reason I have approved all of this is that I find it very important, from an educational point of view, that my son learns to deal with these matters. That he stands up for his opinion. That he weighs up the value of respecting the rules and customs on the one hand, again the value of standing up for something that is so important that it can’t be done according to the rules. At least, that is what I am telling myself. My elephants rider is teaming with integrity, good sense of purpose and rational thoughts. Unfortunately they are all fabrications of my head, and have nothing to do with the reason I said ‘of course you can go and demonstrate’. My elephant went left at the moment he heard ‘it’s for a better climate’ and my rider couldn’t do much else but go along and invent a story.

How would I have reacted if my son had wanted to demonstrate for a stricter immigration policy? Or for more flexible rules around the age limit for games and films? Would I have said just as naturally: yes, it is important to learn how that works, demonstrate? Or would I have reacted differently?

Accuracy and truth, all in all, they are unreliable beacons to organise your life. They absolutely direct my actions, but the question is to what extent I should let that happen. Because if they are actually elephants who instinctively react, why is my truth and correctness better than that of another person?

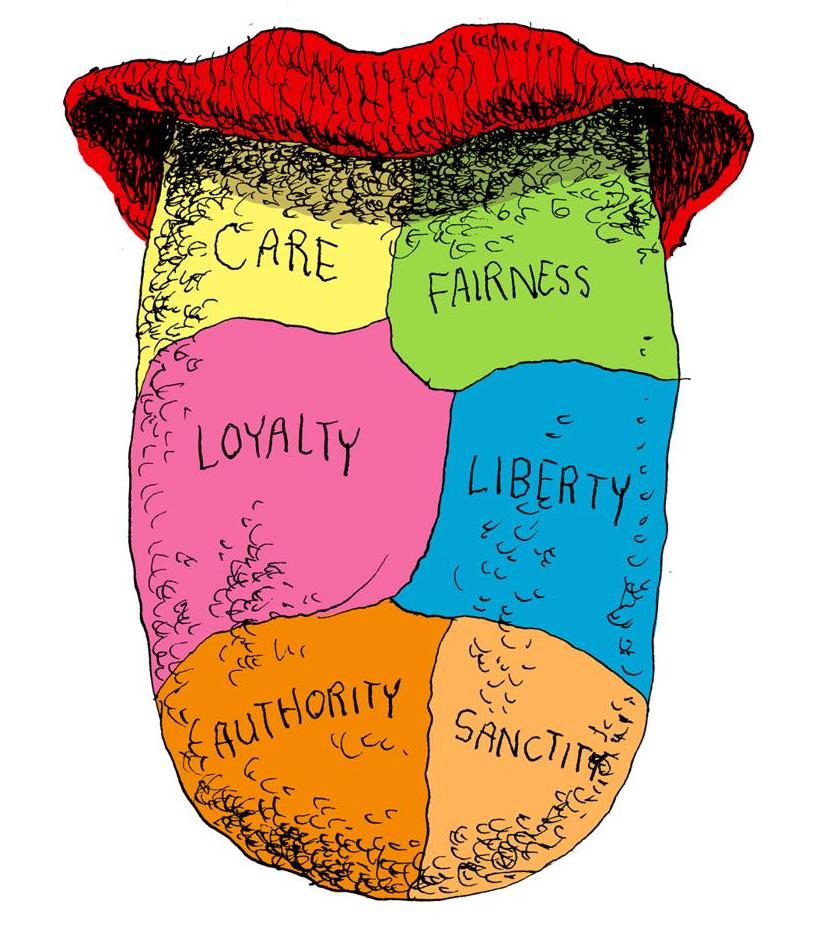

Jonathan Haidt describes in his book ‘the righteous mind’ that all morality consists of the same six ingredients. I have mentioned this before. The degree to which we consider the ingredients important varies between groups. But according to Haidt’s description, there is less light between all our different versions of Righteousness than we think.

If this is so, if this description is correct, then who can appeal to moral superiority? Whose compass is then the most pure? I started my research more than six months ago with the proposition that we all think we are Frodo, but that according to the rules of the story at least half of us were actually orcs. But is that so? How many really bad people do I know? Are our moralities really so different, so easy to score on a ‘good’ and ‘bad’ yardstick?

While I’m writing the previous paragraph, I’m getting restless. Because despite the fact that I believe in the description of Haidt, despite the fact that I see much wisdom in a description of morality as a general shared concept with different priorities between groups, it is difficult to unite my lower abdomen with the consequences. Because morality touches me, on a deep level.

Another example to illustrate this. Again about my son (sorry! Especially for him…). He was once small, three or four years old, when we had this conversation:

Son: ‘Mommy, I know what I want to become when I grow up!

Me: ‘What is that dear?

Son: ‘Well you know, first I wanted to become a firefighter’.

Me: ‘Yes, I remember’.

Son: ‘But you know, that’s a lot of work. So now I think I’ll become a pyromaniac’.

Me: …..

There are many mysteries in this short exchange. For example: how on earth does he get the word pyromaniac? (it featured in an song from the thema park the Efteling.) But at the moment itself my overwhelming feeling was one of powerlessness and a some despair. He was – and is – a clever child. His reasoning that lighting a fire is less work than putting it out, was difficult to undermine. But at the same time I saw in my minds eye where this could lead if he continued to develop his cleverness without ‘moral guidelines’. Or at least without moral guidelines that I thought were good enough.

So for me a very important and difficult question is: How far does moral pluralism go? In the end, can we justify everything? I can start the argumentation, but I already know that I don’t like where it ends. There is – I have – a need for an objective or at least shared ‘right’ and ‘wrong’. I must continue to believe not only in the Frodo’s, but also in the Orks. Not so much because it is true, because they are really there, but because it is necessary to structure my life. To make the group, society, work.

The question is: do we make the differences between our moralities, between our versions of Righteousness, greater than they are? Because that is functional for our society? Because it controls us better as a group, keeps us more together, binds us? And if so: how bad is that? Is it inescapable? Or does it amount to a sliding scale to a tribal world in which the other always has to remain the enemy?

I don’t know. I still think hard on this one. What I do know, is that the fact that Righteousness is less absolute than I thought, touches me even more deeply than the fact that Truth has fallen from its pedestal. Somehow – maybe my scientific background? – I can quite easily accept that Truth is grey. But Righteousness? I’m still working on that…..