A myth is an established belief in something that is scientifically incorrect. I didn’t come up with that definition myself, Stephan Lewandowsky and John Cook described and researched this. Fun fact (actually not really funny) is that the article encountered so much resistance from people who believe in myths, that the magazine has withdrawn the article. Not because the research was bad or the results were not correct, but because it was ‘too sensitive’. 1-0 for the myths, so to speak.

Not everyone is sensitive to believing in myths, but they are extremely persistent and contagious. Once you believe them, they are stuck in you head. And there is even scientific evidence that a myth, even if you don’t believe it, affects your worldview once you hear it. As they say: it can not be unheard. What makes such a theory so darned attractive?

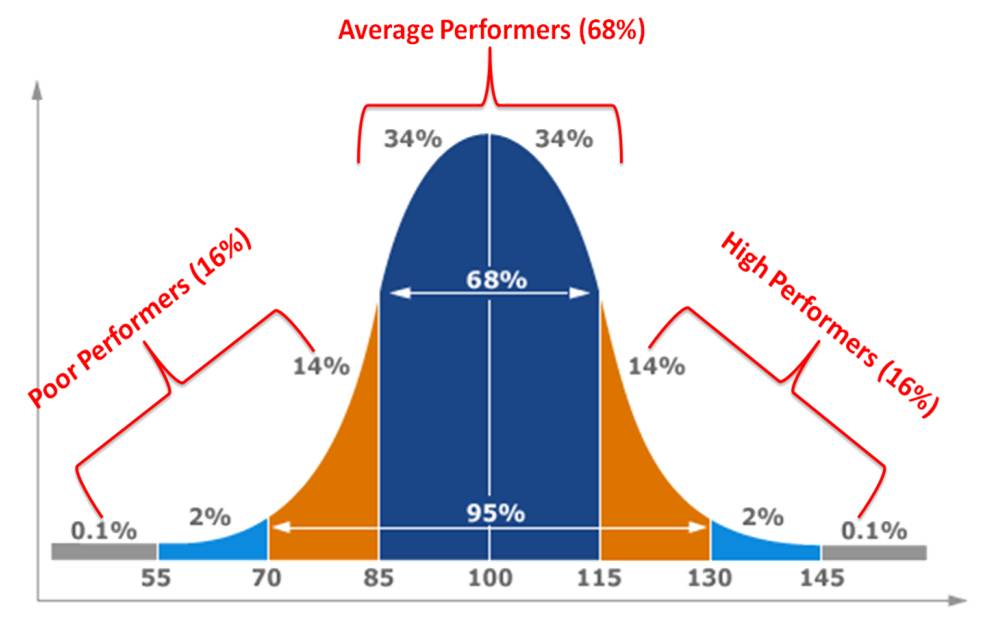

That’s because of all those different shortcuts and preferences in our heads I mentioned earlier. We love facts that confirm our worldview. We see patterns everywhere. We attach more importance to 1 fact that we have experienced ourselves (or that a friend’s uncle has experienced) than to facts with large numbers. Large numbers are scary. And so on and so on.

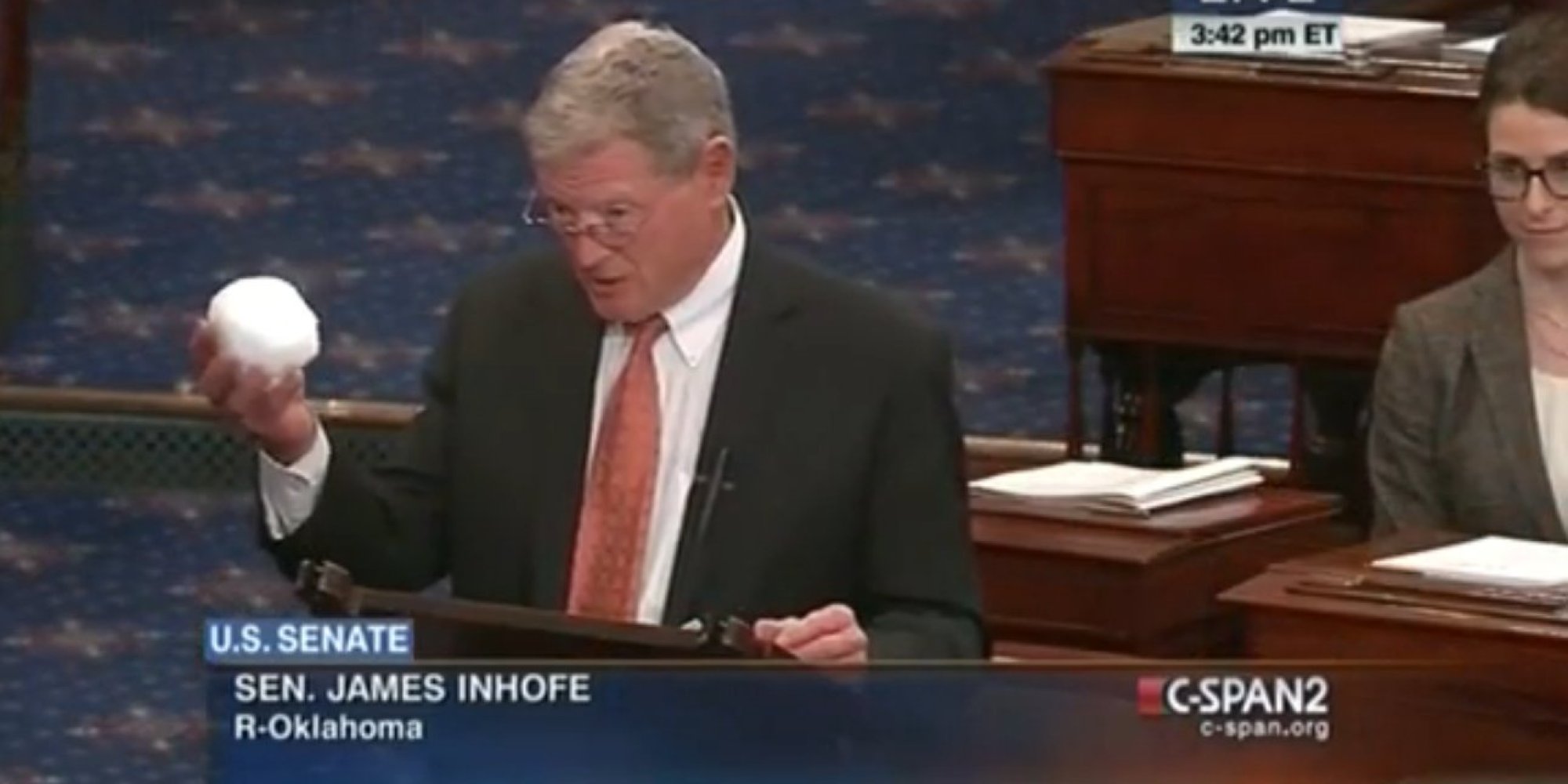

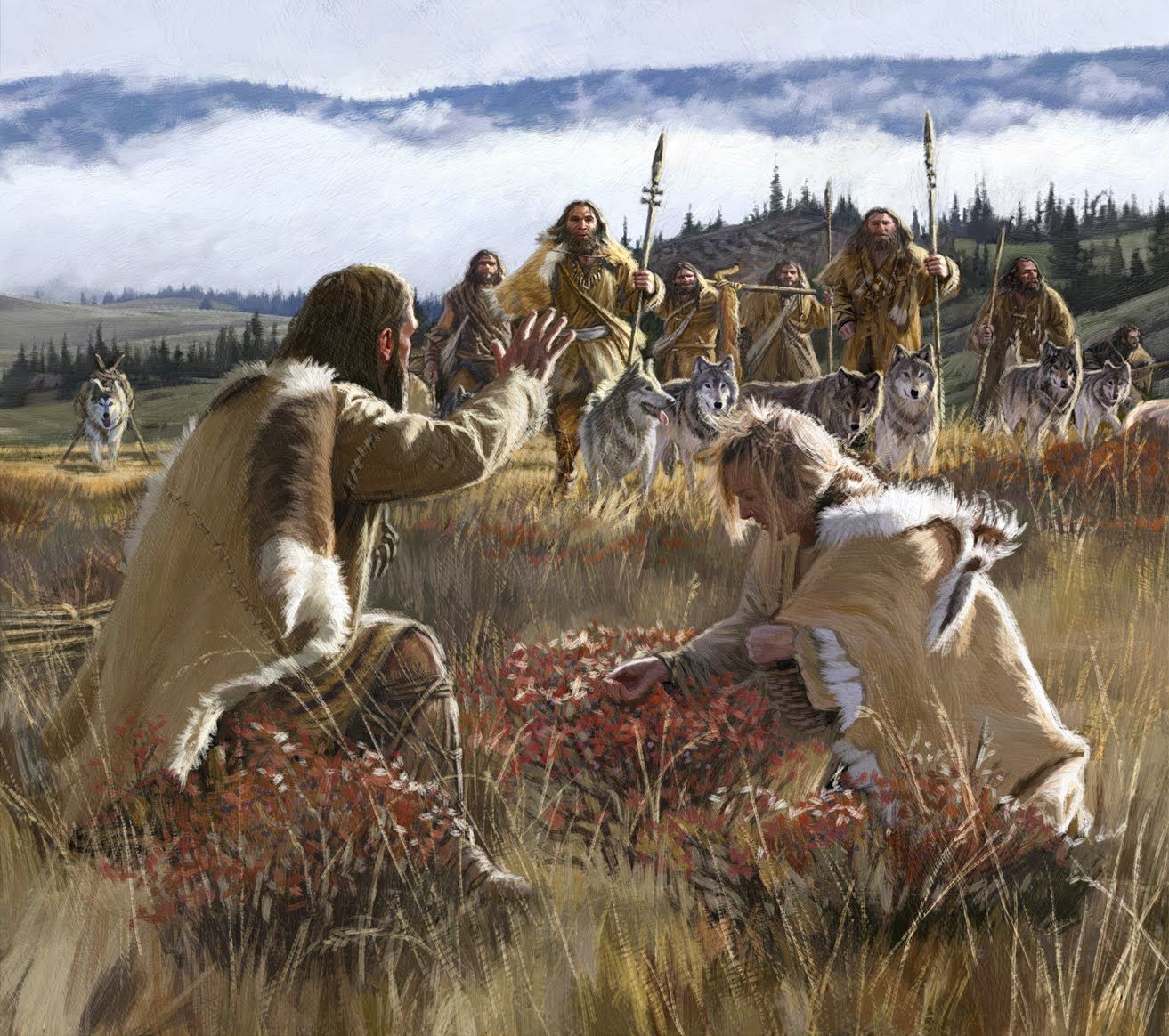

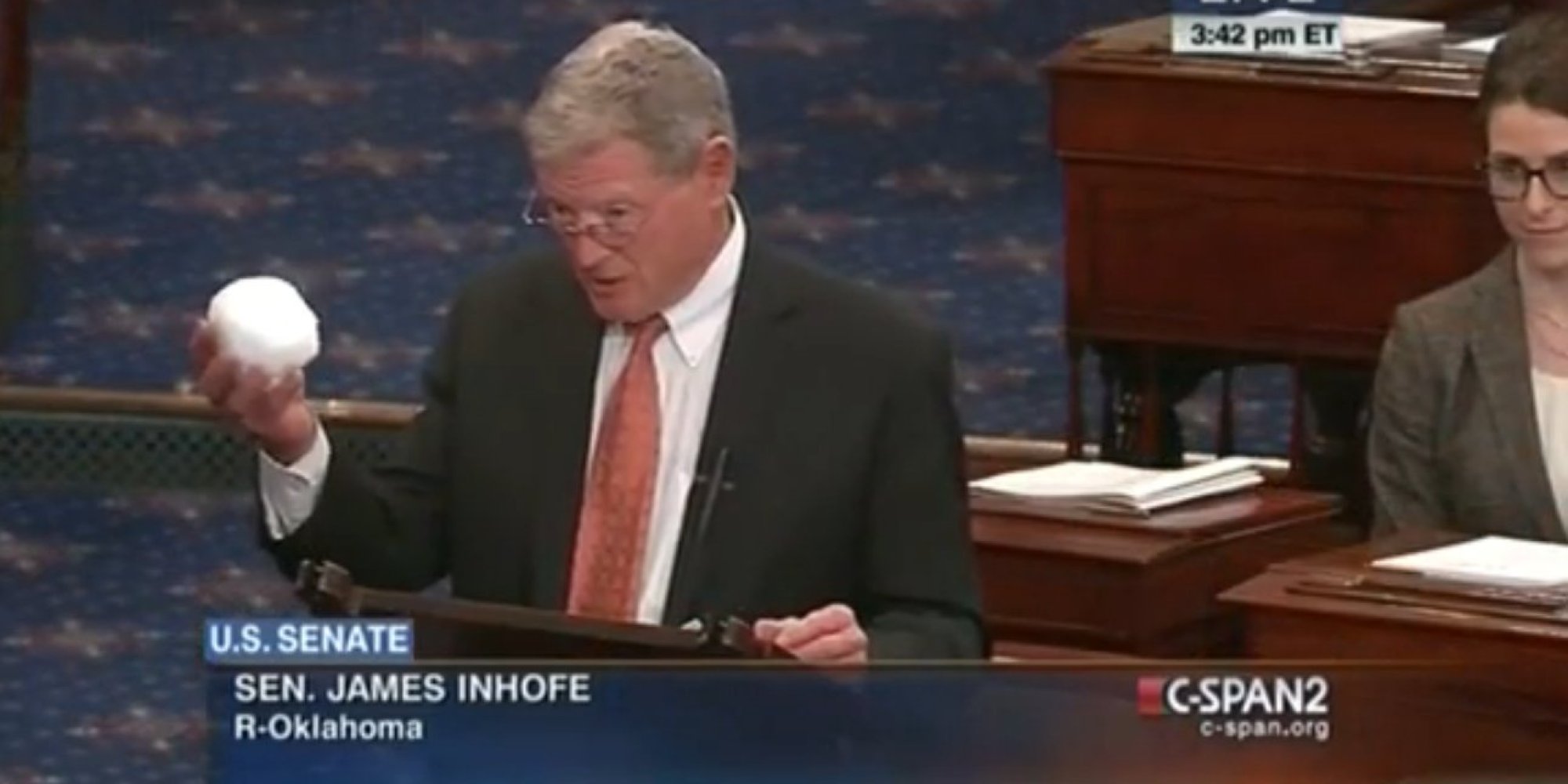

As an example of this is the myth that the climate does not change at all. Why is it so tempting to believe this? Research shows that this myth has an enormous appeal, especially among people with a strong belief in the free market. If you believe that the market is the best organisational mechanism for society, you do not believe that man is responsible for global warming. From a ‘confirmation bias’-view this correlation is easy to understand: because if you would believe in climate change, you would also have to admit that the free market may have some limitations. Furthermore, global warming is, of course, pre-eminently a theory of large numbers, vistas and macro-effects. A snowball on the other hand is close by, tangible and….. Cold. Quod erat demonstrandum.

All these different mechanisms in our brain make that a wrong theory, that feels right (fits our moral compass), fits our worldview, explains patterns we see and comes with facts we can relate to (of that friend’s uncle), is very attractive to remember (remember, Darwin?). And remembering is the first step to believing. Compare it to songs like the Macarena or Sofia or Gangam style, music that gets so stuck in our heads that we eventually find it beautiful.

Besides being very ‘sticky’ to enter our memory, they are also very ‘sticky’ when we try to remove them again. Research has shown that when trying to correct conspiracy theories there is a life-sized danger that you only strengthen the theory in people’s heads. How is that possible?

That too is mainly due to the confirmation bias. And through selective memory. When we pierce a myth with facts, and do so imprudently, people only remember ‘there was something with that myth’. The myth becomes more common in people’s minds, and thus more accepted.

Fortunately, there is help with de-mythisation. There are three simple rules you have to follow according to the ‘Debunking Handbook‘ of John Cook and Stephan Lewandowsky:

1. Focus on the facts, not on the myth.

2. Do not mention the myth itself, or if you have to, warn of misinformation before quoting the myth.

3. Provide an alternative explanation for the myth.

What they say actually comes down to this: mentioning the myth strengthens it. So avoid this. Especially as a title, as a heading or as an introduction. After all: over time, we only remember the titles of things, the facts sink away and the myth remains. Be clear and short: too many facts makes that nothing is remembered. Keep it Simple, Stupid! And use pictures, because we always remember pictures better than words.

Besides the sparse and clear use of facts, they also say that you should always explicitly announce it when quoting untruths (the myth). Make sure you stay away from the ‘somewhere in the middle’ swamp. With that prejudice, people are presented with two opinions (the climate changes as a result of human action, and the climate does not change). Despite the fact that one opinion occurs much more often and is better substantiated, your brain mainly hears ‘there are two opinions’. The automatic reaction of your brain to that is: the truth will be somewhere in the middle.

Finally: give an alternative. People are much better off disbelieving something if they have an alternative that they can store in their brain it its place. Just think how much easier it is to believe that your son hasn’t taken a biscuit out of the biscuit tin if you find out that your husband was hungry last night. That knowledge works much better than the sweet eyes of your child that declares to have ‘really done nothing’.

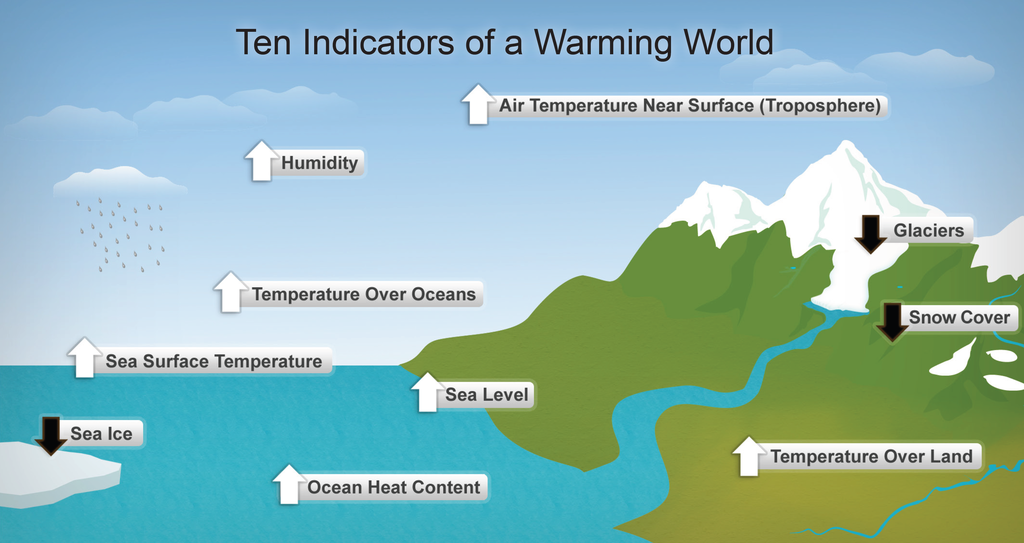

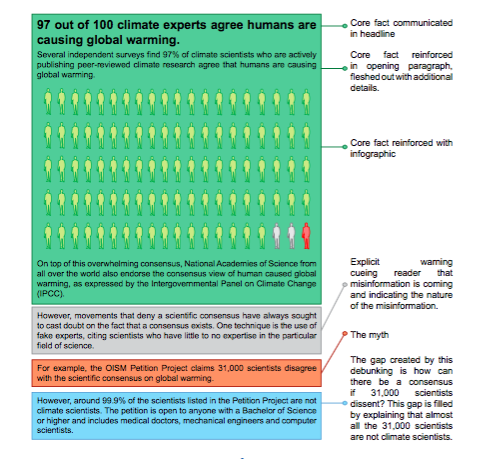

Back to climate change. How do you tackle that, as a myth piercer? John and Stephan have used their rules on this specific myth. And write the following article:

See how the fact is the title, not the myth. See the beautiful infographic. See the warning, that explicitly announces that untrue information is coming. And finally, see the alternative explanation. All the ingredients for a true myth piercer, stuck together. Believe me, it works!

Oh, and do you know what works (even if it feels a bit crazy)? Before you confront a myth follower with the facts, let him or her tell you first about what is good about them. The better a person feels about himself, the easier he or she changes his or her mind. Bizarre maybe, but really true.