I promised I would tell you a little more about my favourite fallacy: The Gamblers Fallacy. This fallacy reasoning, this shortcut in our heads, is based in the fact that we are so bad at dealing with coincidence (read: Welcome to the Matrix for more about this subject).

The gamblers fallacy is easy to explain: imagine you’re at the casino’s roulette wheel. The last 4 times the ball has landed on a red number. What do you do when you bet? You gamble on black, right? Because ‘it’s due’!

Another good example also comes from inside the casino. You see people standing there for hours and hours with the same slotmachine. Because, as they say: this one is due a jackpot! What they mean is that the gambling machine hasn’t had a big payout for a very long time, so it’s ‘time’ for the jackpot to fall.

As you all know from my previous blogs, coincidence is really coincidence, even if we don’t want that. The chance that the ball wil land on a black number is (a bit less than) 50%. The chance that the jackpot will fall is as big as the slotmachine has been set at (and trust me, that chance is not that high). These odds only change if you adjust the machines. Not if you use them more often.

The tricky thing about this fallacy is that it is about chance, but also about statistics (the science of collecting and comparing numbers). And our head is not built for numbers (read more about that in Hans Rosling’s factfulness). We’re bad at crunching numbers, we pull them out of proportion and make them into something with an emotional or at least normative value (much! little! dangerous!). While statistics collects and calculates, we feel and draw conclusions.

Take the teacher who compliments a student with a particularly high grade for an exam, just to see that this student is doing worse next time. While the student he gave a telling off for an incredibly bad grade does better next time. The teacher draws the – emotionally very logical – conclusion that students are more affected by punishments than by rewards. While the effect of statistics on these second series of grades has probably had a greater effect on the grades, than his rewards and punishments.

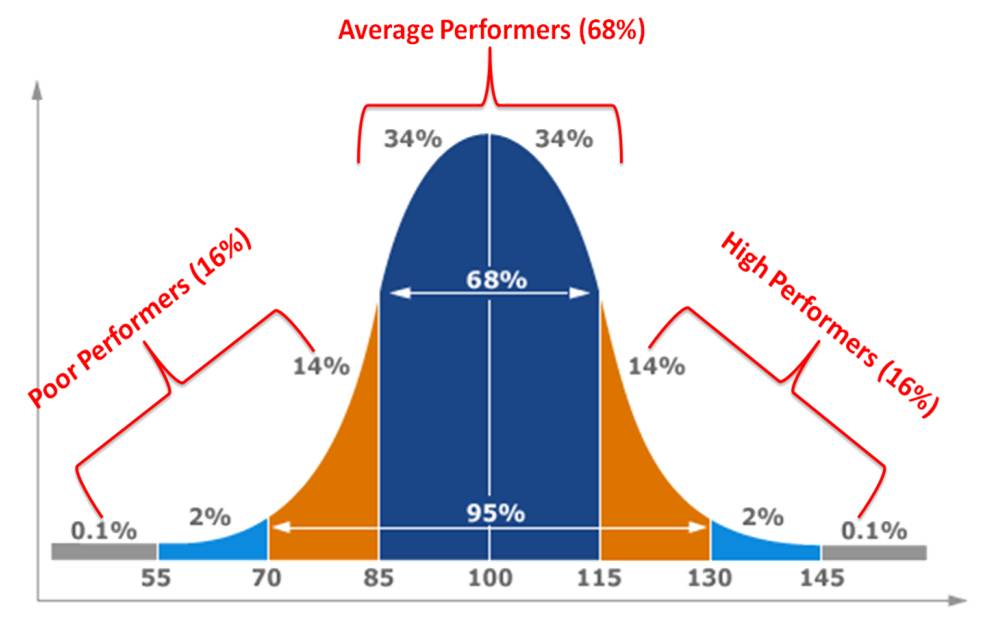

The effect of statistics on these two students works as follows: there is an average score for all students at an examination. A student with a deviating high grade has a higher chance of scoring more average next time (in the picture below 68% of the students score average) than he has of scoring such a deviating high grade (16% of the students score deviantly high). The student with a deviating low grade, also has a higher chance of scoring more average (68% chance) next time, than that his chance of another deviating low grade. The law of averages is much less intuitive, but for the teacher probably a stronger prediction of future results, than his reward or punishment policy.

Disclaimer: I am not trying to say that studying does not help improve your grade. That is the difficulty with statistics: the conclusions are always about larger groups and averages. And on average, the chance is higher that you get a grade somewhere in the middle of the curve.

Isn’t it strange? It feels like we’re all suddenly living in a lab. Of course, we all understand that when we throw a coin in the air a lot of times, about half of the throws will be heads, and half will be tails. But that we are coins ourselves, subject to the same laws of chance, the big averages and the probability calculations, that feels strange and unnatural. And yet that is the consequence of accepting that so much in our lives does not happen for a reason, but in coincidence.

So the next time you think: it must go well/bad now, because the previous couple of times….. Then stop yourself and smile in a mirror. And take a coin from your wallet to throw it up. Just to make it visible that what will happen that day depends to a large extent on chance. Of course that’s scary, but secretly it’s also quite liberating: after all, it’s there is that much coincidence around you, not everything is entirely up to you anymore. Kinda nice, right?

For lots more on statistics, and how to use it in the decisions you make, visit the website of poker champion and science fan Liv Boeree. Or, if you just want to spend 6 more minutes, please see her TED talk on ‘three lessons on decision making from a poker-champ’.