Are you trekkies? No? In the Star Trek series, the Borg are notorious enemies of the Federation of United Planets. Somewhere far into the future, when we have settled all our inter-planet quarrels, they are the new external enemy. the Borg are a super efficient race that solves differences of opinion in a very special way: every new ‘member’ of the group is fully assimilated and can no longer think independently. The group and its survival is literally always more important to the Borg than the individual interest.

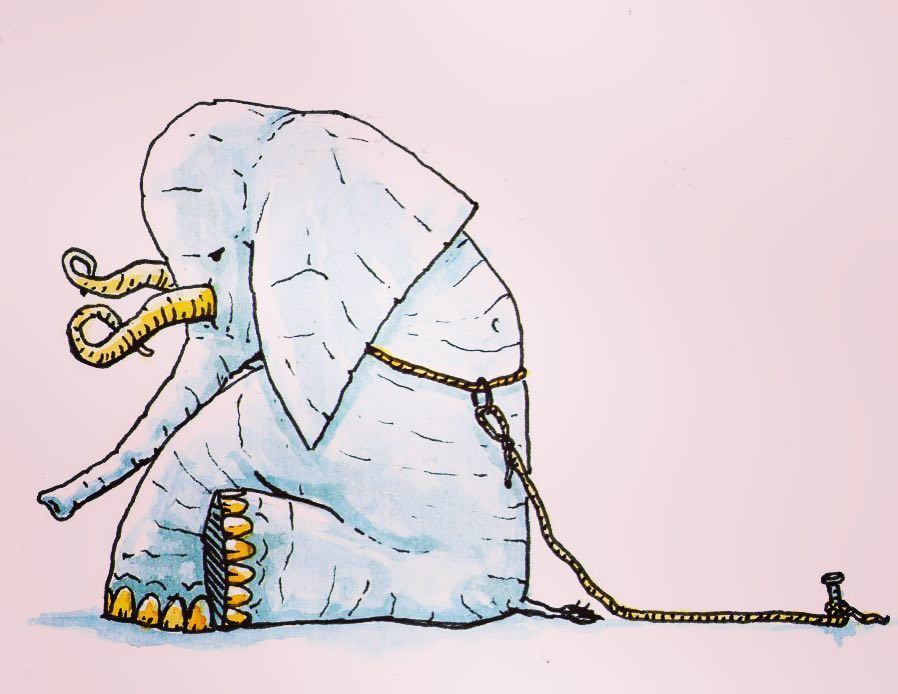

Over the past few weeks, I have increasingly argued that we, as human beings, are also secretly some kind of Borg. Our default solution to problems? Form a group and give them a common goal. I do it myself. I have been teaching cooperation for years. Neighbourhood teams, managers and professionals come to my classes and are taught how to work better with others. What I actually teach them is assimilation. Find a higher goal that you all agree on, be strong together against your external enemy and above all: don’t be too solitary, but feel part of the group. Group interest before everything, wrapped up as a motto that no one can ever be against: ‘Every child counts’ or ‘No youngster should be homeless’.

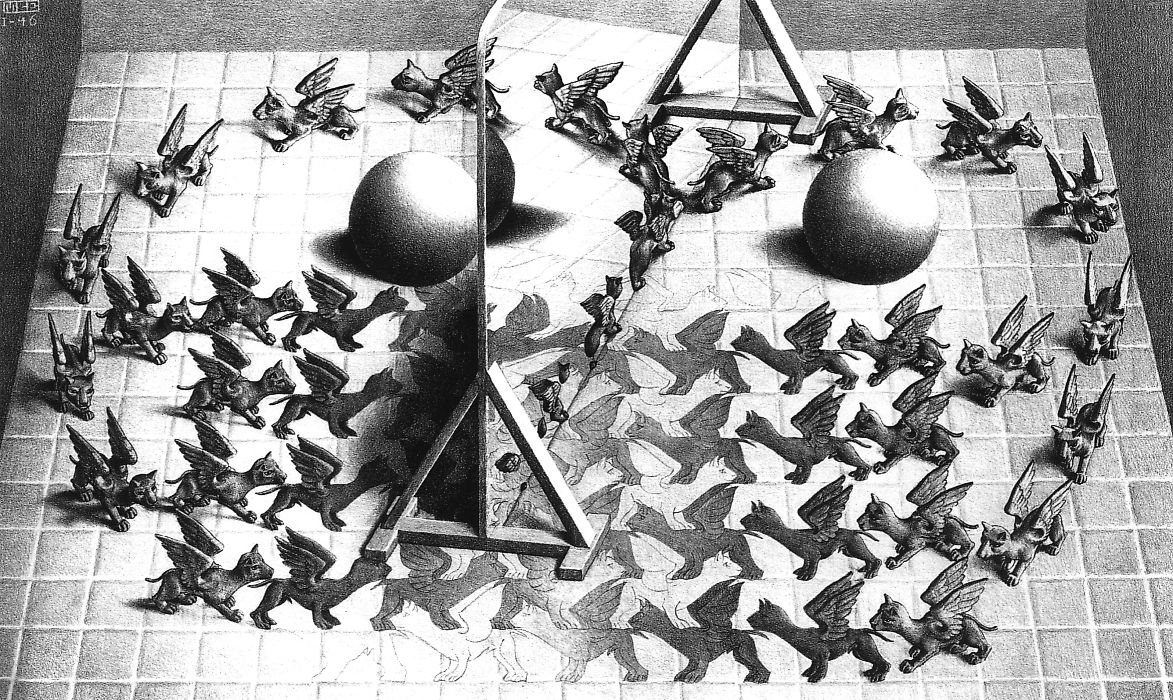

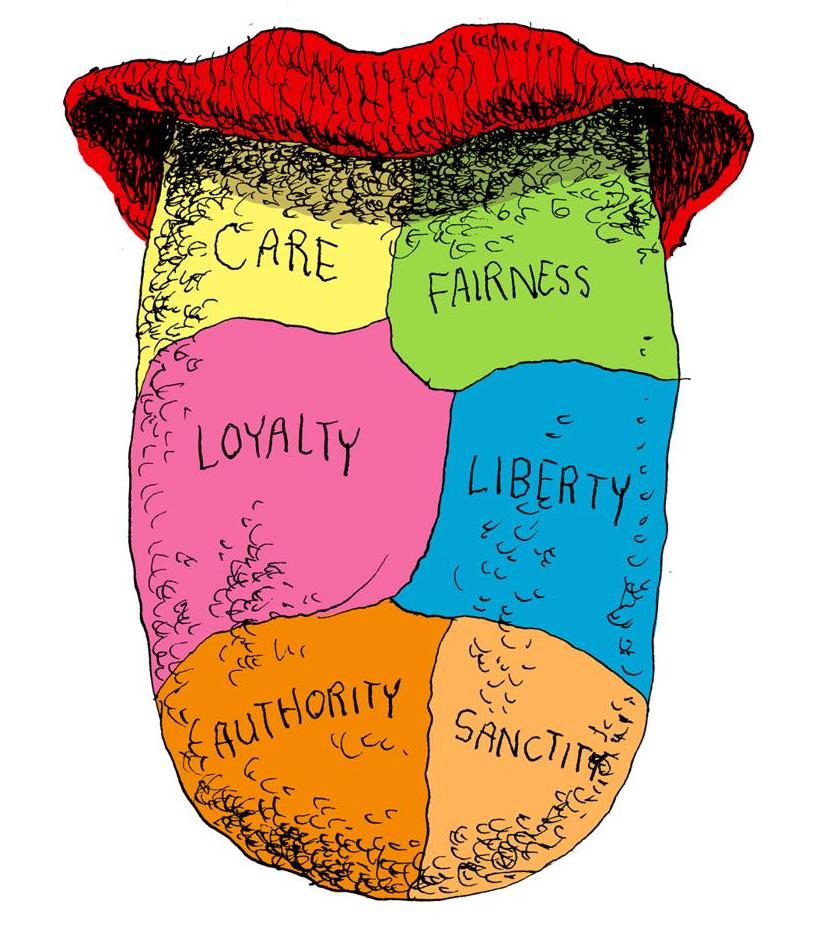

Actually, as a ‘cooperation expert’, I’m cheating pretty badly. After all, what is the most difficult thing about cooperation? Working together with people who do not agree with you. Working with people who have different goals, different interests. Who see the world differently than you see it. And with famous tricks from sociology and psychology I avoid these difficulties. Aren’t the interests equal? Look where they do overlap. Is someone’s interest at odds with yours? Find a mutually important contact with an intermediate interest and form a broader cooperation. All the tricks I teach are aimed at one simple principle in sociology: people are incredibly good at forming groups, and incredibly loyal to groups of which they are a part of.

This way of working together has worked quite well so far. It’s true

that you end up with people who have to be your enemies: those who don’t (yet) belong to the group. But that’s an acceptable cost in a fairly stable environment, where you can choose your enemies and your friends wisely. Where relationships are fairly constant and durable.

In 2019, however, we are well on our way to a network society: a society with ever broader, more volatile, changing collaborations. More and more often, we have to cooperate with ad hoc parties, with varying partners, in occasional cooperatives. It is no wonder that the members of the neighbourhood team that I train are increasingly frustrated with what I teach: once they have finally built up a good relationship with someone or something, their function or the working relationship will likely be changing again. Where are the stable relationships when you need them?

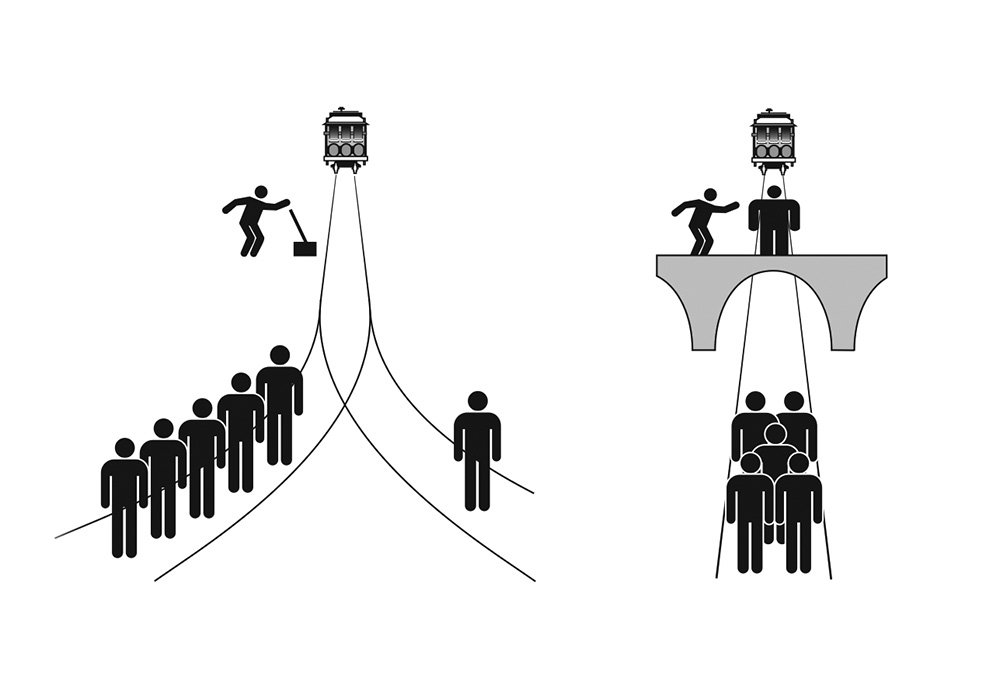

In this new constellation, we need new ways of working together. Ways that continue to work robustly, even when you don’t have a shared goal. Enabling cooperation between people with different points of view and interests. Which are not mainly based on the mechanisms of group formation. But they also do not rely on the mechanisms of economic negotiation alone: back to cards-on-the-chest, ‘I win so you lose’, zero-sum negotiations. Because that is all we seem to have at the moment when forming a group fails: distrust, a culture of negotiations and trying to win.

There’s gotta be something in between, right? Something between ‘we’re friends’ and ‘I’m a rat’? Something between marriage and a one night stand? A lat-relationship or something?

That’s what I’ve been looking for lately: what are the mechanisms of collaboration in a network society? How do we arrive at an honest and open discussion about interests and points of view, without having to agree? How do we get past the polarisation that we are currently seeing in, for example, the climate debate? How do we tackle the major dilemmas of our time, for which we really need each other, but for which we also know that we will never be able to agree?

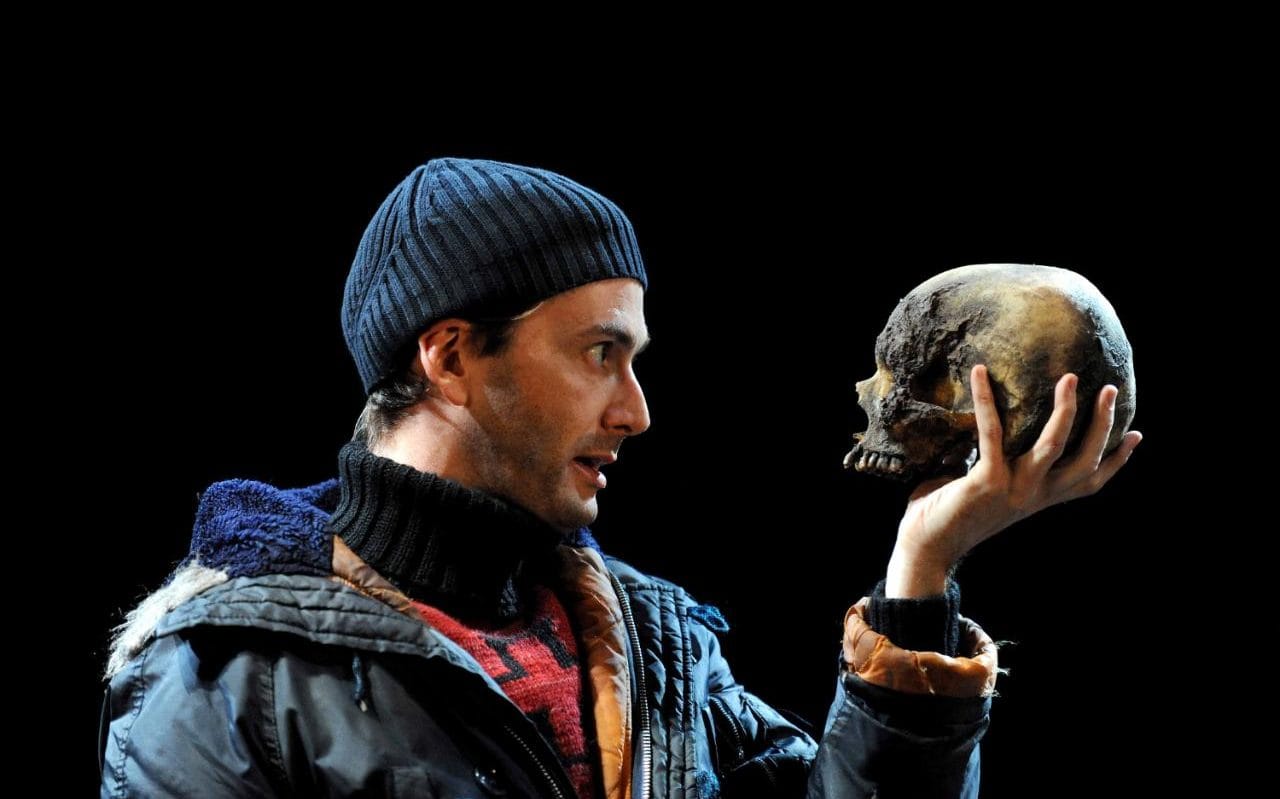

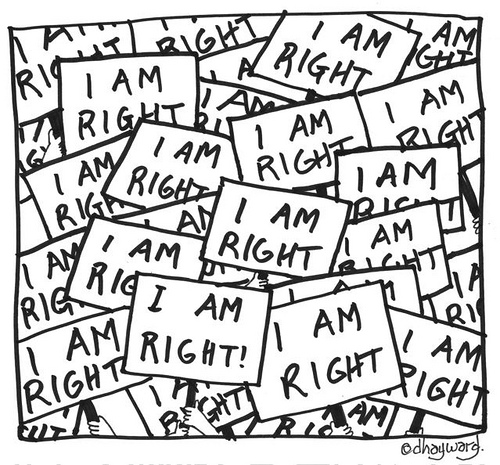

I don’t have a definite answer yet, but I think we should build that answer together. I already have a start: gentleness and doubt. Words that are currently classified as ‘soft’ and ‘naive’, but I don’t think they are. Rather ‘powerful’ and ‘solving’.

Doubt is so incredibly important when working together in a network society. If we have more doubts about the correctness of our own views, if we leave a little more room in our heads for other points of view, we give ourselves the space to look for solutions in a more flexible way. And what about that mildness? I don’t mean it only in the sense that we should be mild in regard to the opinion of others. As essential as it is to be milder towards others, mildness begins with yourself: allow yourself to be unsure. To not always be right. To not always see it right. We are not perfect, which is normal and logical. The sooner we can accept that, the sooner we can start practicing working together in a durable way.