Last month in America last month there was a scandal about how unfair the selection at the prestigious universities is sometimes: famous and rich people who bought buildings for the university, after which the child was admitted. These scandals not only show the extent to which wealth corrupts, they also send a signal to people who are unable to buy a place at a university: there are different rules for people who are rich and powerful.

And that is a problem. Not only because of corruption, by the way. This article in the New York Times explains very clearly why the selection process of the prestigious universities is already a problem even without corruption. To enter such a university, a student must meet so many requirements that often a large part of the school time and energy is used for ‘curriculum building’. Students and their parents work for years on activities, grades and CVs that lead to a greater chance of acceptance. It goes without saying that here again, especially the wealthier people have greater opportunities to actually be able to carry out all these activities. But an even bigger problem is perhaps the gigantic narrowing of the field of vision of these students. Their self-worth, personal development and their childhood entirely in the service of a good university.

In the Netherlands, we do not have such selection processes. Although; my neighbour boy was admitted to a student association this year and I can’t say this admittance was due to a reasonable and well-considered selection process… Here too we seem to place a lot of value on belonging to a select group of people And here too it constricts our view of what a successful study and working life is.

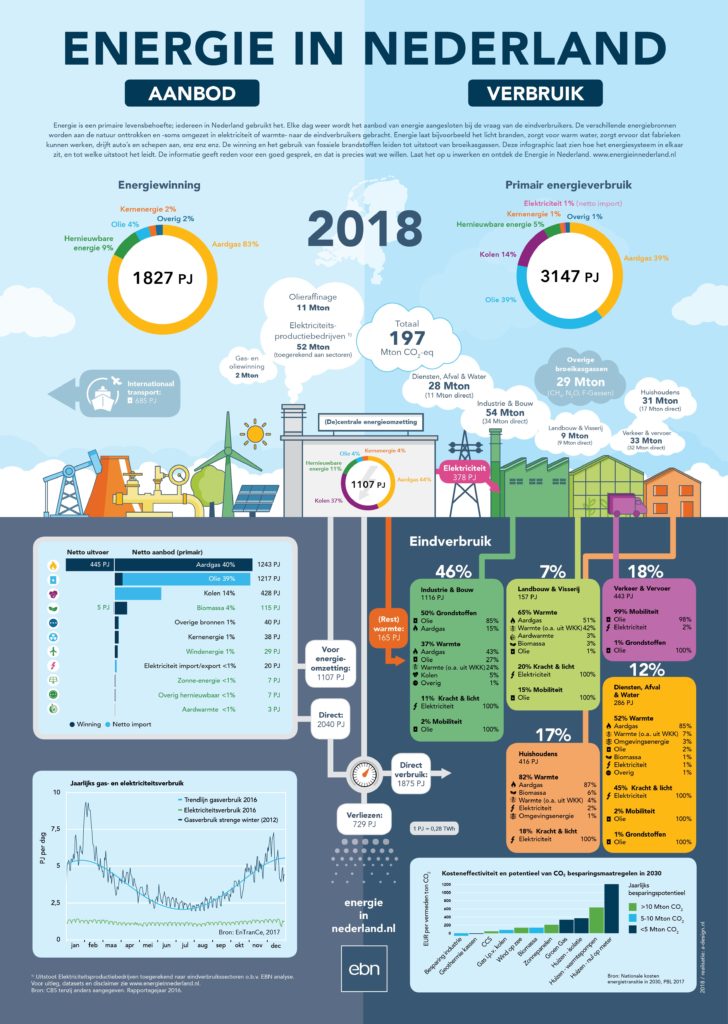

In the Netherlands we also are keenly aware that different rules apply to rich and powerful people. Take the dissatisfaction with the climate agreement, where companies (which clearly use more energy than households, see infographic below) seemed to be excluded from the measures. The discontent in the country was strongly felt, and also visible in the latest election results (where I do not want to state that the election results are a direct result of the climate agreement, there is of course much more happening that affects election results).

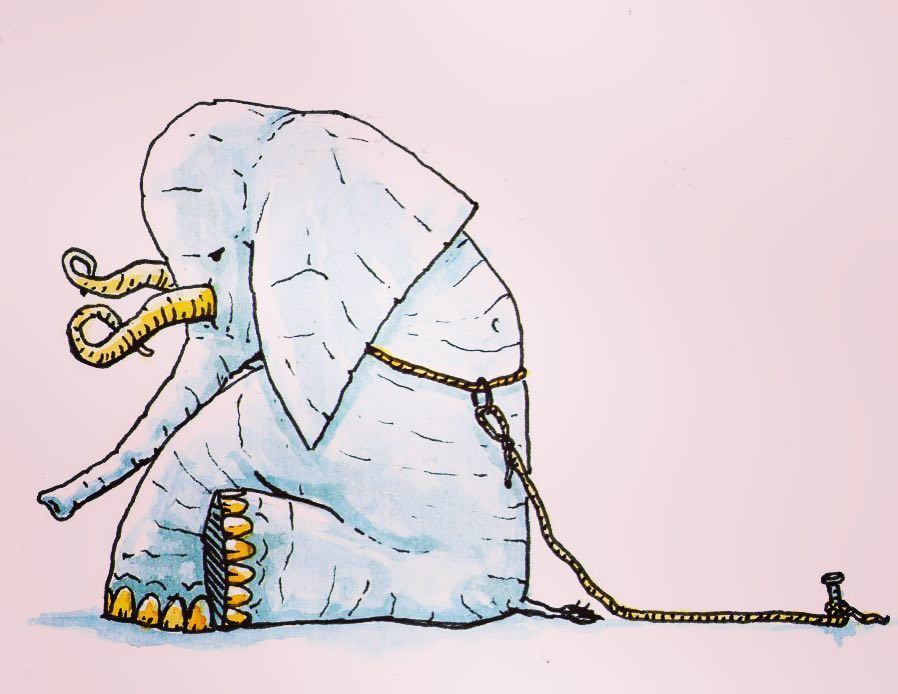

In a book I recently read, ‘Hillbilly Elegy‘ by J.D. Vance, it is described beautifully what is so bad about the image that there are different rules for rich and powerful inhabitants. The problem is not so much that they – the rich and powerful – get their way easier and more often. The problem is much more that the non-rich and not powerful get the feeling that it doesn’t matter what they do or decide. A system in which it is easier for one group to move forward also means that there is a group for which this is much more difficult. For that group, their own commitment and making smart choices is disconnected from success. And once that has been disconnected, why should you still commit yourself?

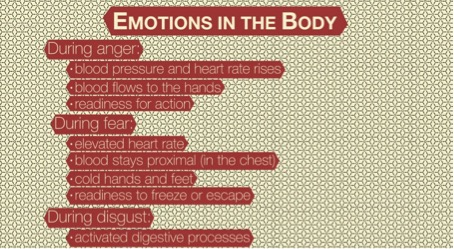

Learned helplessness, they do call it. Nice term, but a less beautiful phenomenon. Because if you no longer think that your behaviour matters, then the world becomes a very desolate and hostile place. If you feel that you are no longer the owner of your own destiny, you can feel enormously powerless. In Hillbilly Elegy Vance describes the consequences of this powerlessness: lethargy, externalisation of one’s own bad situation (it is always someone else’s fault) and above all, far fewer opportunities and possibilities. A vicious circle of powerlessness leading to a negative spiral of life chances.

In that light, I am extremely happy with the results of the last elections in the Netherlands. Because never before have so many people voted in provincial elections. People who take their fate into their own hands, who don’t feel so powerless that they think it doesn’t matter anymore. They want change and take action for it themselves. My hope is that these people will feel taken seriously in the coming period by their elected representatives. So that they notice that they are indeed not powerless, and that their decisions are absolutely influential.

And is it then too much to ask to hope that we have now also finished making each other small and blaming each other? That we see this election result as the last push in the right direction to really listen to each other and take each other seriously? Everybody – from liberal to conservative, from woman to foreigner – deserves this respect.