People are pattern-searching engines. Take those M&M’s from the previous blog. Whether you like it or not, you’re looking for a pattern. Someone said to me: ‘There must be a pattern in it, right? Otherwise you wouldn’t have put the picture on your blog’. The belief that there are patterns in almost everything is embedded deep in our system. Whole websites exist for people to share their pictures of clouds, buildings, dustbins and so on, all with faces on them.

This raises two questions: Why are we so ardently looking for patterns? And more importantly: why is that (sometimes) a bad thing?

The first question: why are we looking for patterns?

A common theory goes like this: in the past, when we lived on the plains and hunted mammoths, nature around us was very ‘coincidental’. Nothing stood nice and straight and angular. Danger was not neatly framed and bordered with signs. We had to find danger. Did we saw stripes somewhere in the grass? Chances are that it was just a coincidental pattern, but still: if it was a tiger (or whatever kind of striped predator lived back then), the price for ignoring the pattern was very high. And the price for erroneously running away from the striped grass was manageable. It must have been a simple cost-benefit analysis in our brains, which over time has perfected our pattern-finding system. And with success: we still exist as a species. We still see patterns (and faces) everywhere and still it is usually not someone or something that wants to eat us. But the cost-benefit analysis is still positive.

Which leads us to question two: why is it sometimes very bad that we see patterns everywhere? What is wrong with the simple entertainment of the optical illusion or seeing faces in a manhole cover? Surely that is innocent entertainment?

In itself, seeing those patterns is harmless. The problem is not in mistaking the the ‘simple’ ambiguity of an optical illusion or whether or not to see a rocket in the sky. The biggest problem of our addiction to patterns arises in situations that are not just ambiguous, but multi-interpretable. Real life, so to speak. Is that colleague smiling at you sincerely? Or is he looking mean at you? Is there a reason why it always starts raining when you want to go outside, or that you get a headache from talking on the phone? We are searching all day long for patterns to make our world understandable.

That search for patterns in ‘real’ life is necessary and helpful. But we take those patterns a bit far. Especially in situations of uncertainty and extreme emotions (fear, happiness), our interpretation machine sometimes runs wild. Evolutionarily speaking, of course, still very logical: especially in situations of danger, the pattern-finding machine had to save your life. But still: in today’s society this sometimes results in a lot of misery. People follow their pattern-searching-machine to the most extreme theories, because simply stated ‘It can’t really all be a coincidence’.

If something happens, especially something very good or something very bad, then we have to find an order, a reason. And faces with that pressure, our pattern-searching machine is our best weapon to order quickly, to understand quickly and above all: to quickly get back on solid ground. The problem? The patterns we find are always based on the worldview we already understand, already know by heart, already accept. I don’t know anyone who sees patterns of unknown objects in clouds, or who recognises new inventions in buildings. With the help of our pattern-finding machine we rebuild the world back to our existing point of reference. We rebuild the world as long as it looks like we know it. Safe, familiar and conservative.

The reason we hold on to our known world and patterns in this way is that the alternative to our head is much worse. If we do not find patterns, we will have to accept a new reference point. A very uncomfortable reference point. Namely that a lot in our lives is nothing more than a coincidence. The peanut butter sandwich that falls on the smeared half? The walkman you forgot to give back after borrowing, from the person who eventually became your husband? Your baby that died? The thunderstorm when you didn’t have an umbrella with you or the sudden sunshine when you had left your sunglasses at home? All of them just stupid coincidences.

Seeing and acknowledging coincidence is so difficult because we find it scary, seeing it as something negative. Many religions are based on the idea that coincidence does not exist. And in science everything is done to eliminate coincidence. Recognizing how much coincidence there is in our lives, would completely destroy the entire book and film industry (And then? Oh, coincidentally it went well. The End). Coincidence is elusive, incomprehensible and therefore taboo. We prefer to keep quiet about coincidence completely.

And so, bit by bit, we have learned to disregard coincidence completely. As Robert J. Tibshirani, a statistician at Stanford, explains: You are surprised when you get dealt a royal flush at poker. And you’re right: the chance of getting those cards is very small. But at the same time the following is true: the chance of ANY set of five cards you get is very small. You only notice it if the set is very good (or very bad). And if you get a royal flush twice in a row? Then superstition is born and every time you play poker you put on your ‘lucky shirt’. Because that really can’t be a coincidence…..

A brilliant illustration of our aversion to chance, especially at very good or very bad events, you can read in the article ‘The Odds of That’ by Lisa Belkin in The New York Times. She tells us about the terrorist attack of 11 September:

‘In the past year, there has been plenty of conspiracy, of course, but also a lot of things have “just happened. And while our leaders are out there warning us to be vigilant, the statisticians are out there warning that patterns are not always what they seem. We need to be reminded that most of the time patterns that seem stunning to us aren’t even there. For instance, although the numbers 9/11 (9 plus 1 plus 1) equal 11, and American Airlines Flight 11 was the first to hit the twin towers, and there were 92 people on board (9 plus 2), and Sept. 11 is the 254th day of the year (2 plus 5 plus 4), and there are 11 letters each in “Afghanistan,” “New York City” and “the Pentagon” (and while we’re counting, in George W. Bush), and the World Trade towers themselves took the form of the number 11, this seeming numerical message is not actually a pattern that exists but merely a pattern we have found. After all, the second flight to hit the towers was United Airlines Flight 175, and the one that hit the Pentagon was American Airlines Flight 77, and the one that crashed in a Pennsylvania field was United Flight 93, and the Pentagon is shaped, well, like a pentagon.’

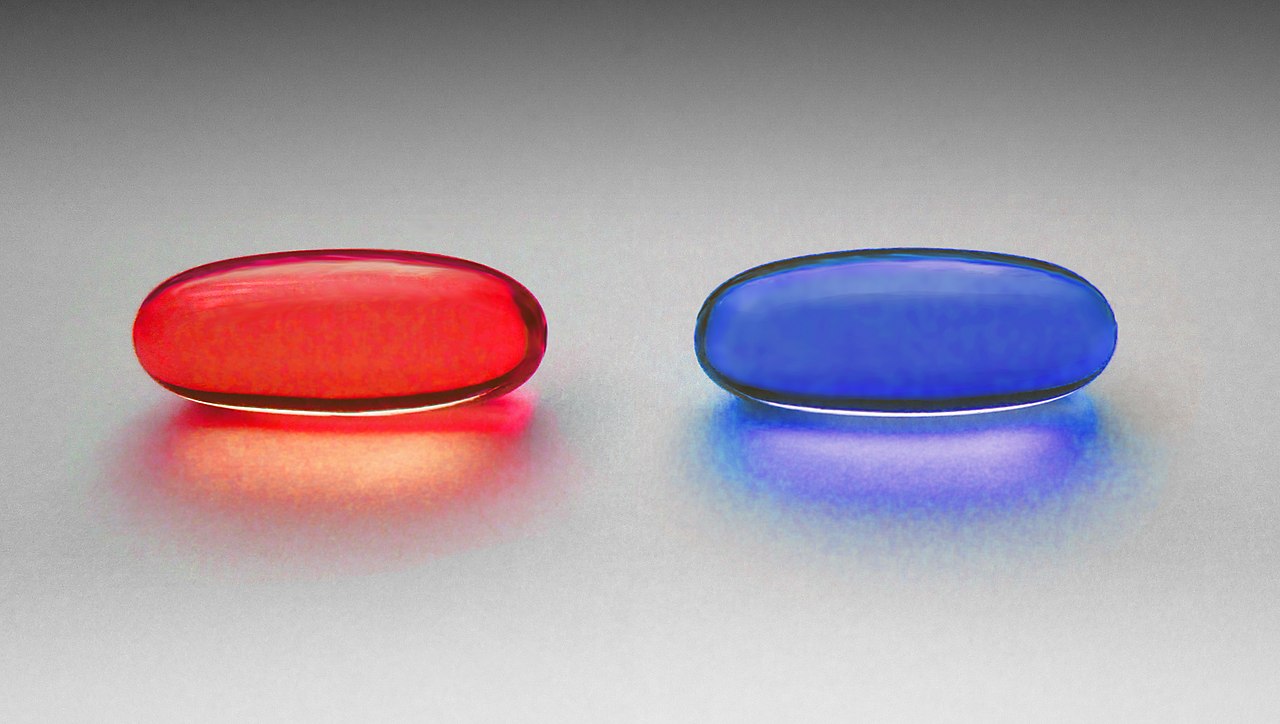

In the end, this did not turn out to be a blog about patterns, but about coincidence. And about the bad reputation we’ve given coincidence in our society. Coincidence is elusive, incomprehensible and therefore taboo. And so we condemn ourselves to our patterns-finding machine and to the world as we have always known it. We take the blue pill and live on in the safe, predictable world.

Links:

The Matrix, a science fiction film about coincidence and patterns: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0133093/

Lisa Belkin’s ‘The Odds of That’ in The New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2002/08/11/magazine/the-odds-of-that.html

The art of everyday thinking: https://courses.edx.org/courses/course-v1:UQx+Think101x+2T2018/course/