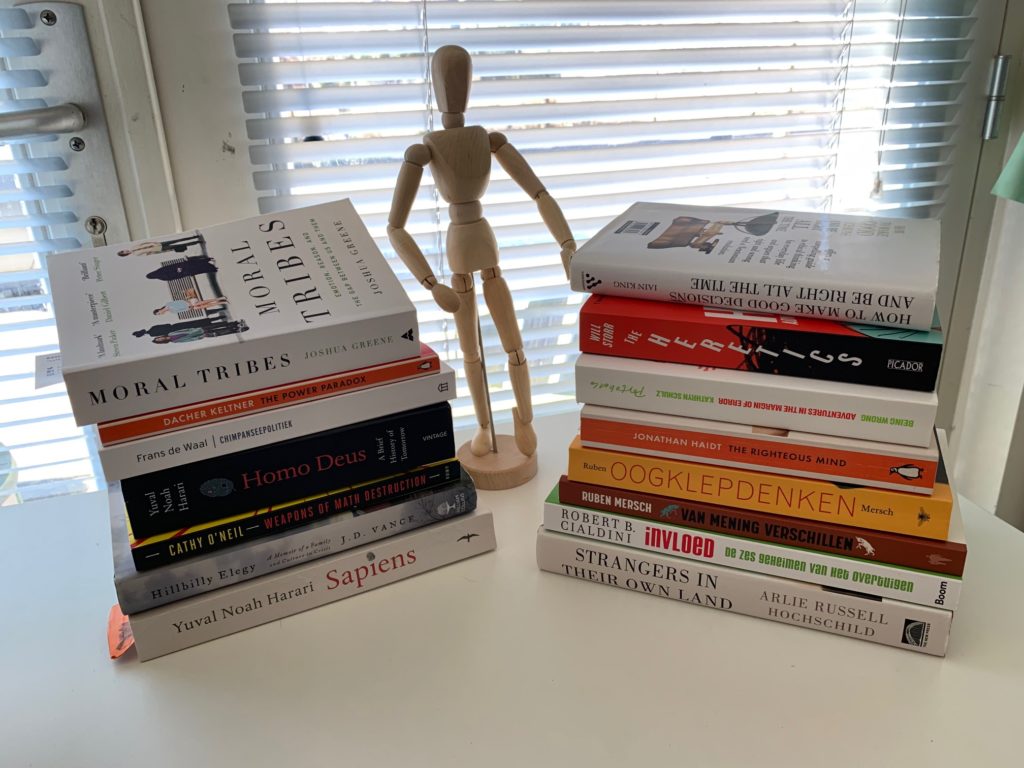

In my research I have collected piles of books. Partly on my e-reader, but I found out that I liked it better to devour paper books. And so there are piles of ‘real’ books on my desk. Some already read, some still waiting to be (re)read.

One of those books was a book with the beautiful title ‘How to make good decisions and be right all the time‘. This book was ‘set to be read’ last week – I try to get at least one book a week from the left ‘still to read’ stack to the right ‘already studied’ stack. I was looking forward to reading it, because, especially considering my blog on morality last week, I’m pretty much looking for the shades of grey and clarity around this subject. Morality fascinates me enormously.

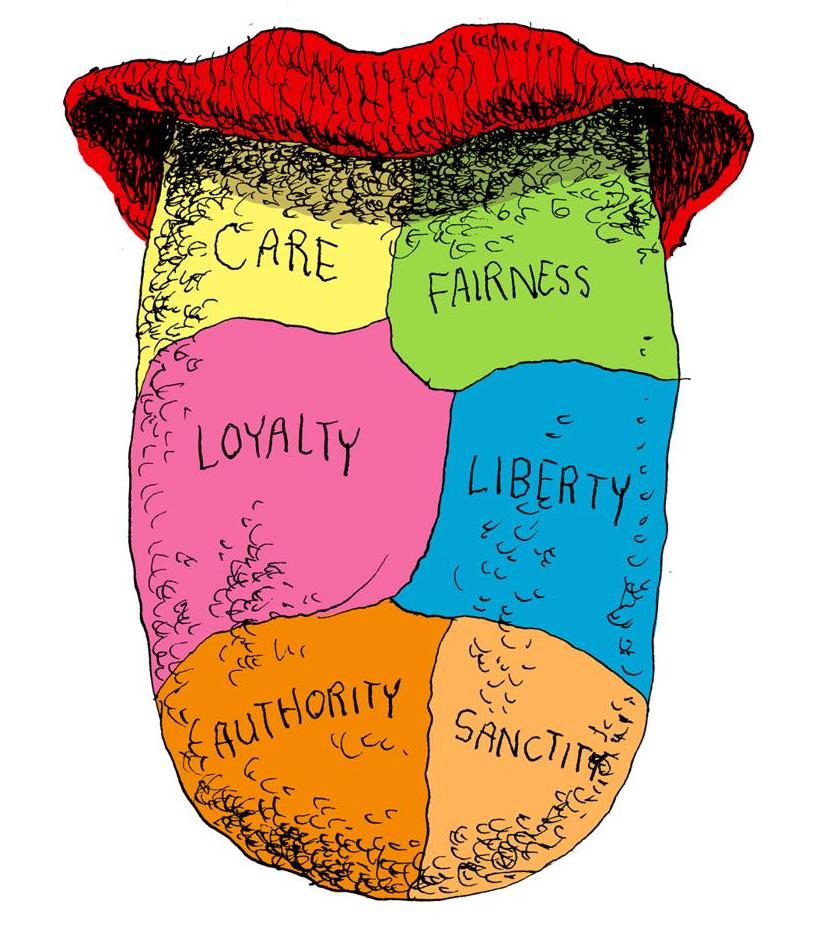

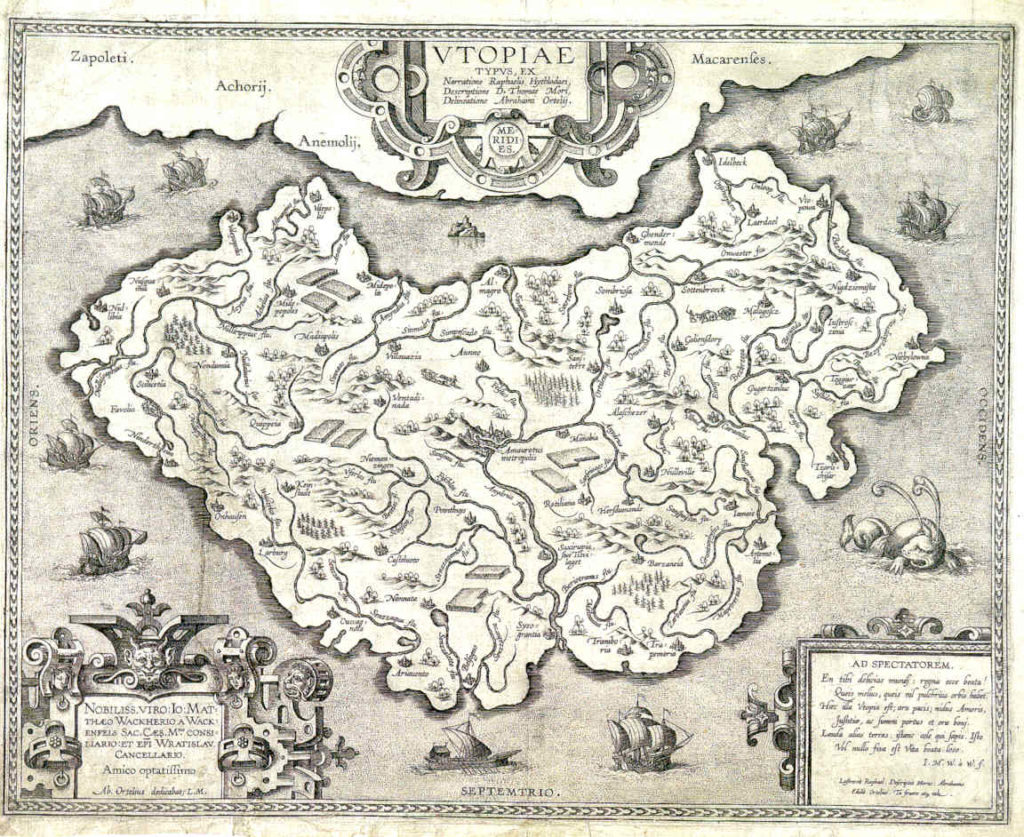

I expected the title to be ironic. After all, everything I had read so far had strengthened me in the opinion I expressed in my blog last week: morality is full of shades of grey and it is quite difficult to find a certain viewpoint that is ‘better’ than the other viewpoint when there are moral differences of opinion. Always being right therefore, as the book promised, seemed to me to be a utopia (also a beautiful book by the way, I should add it to the ‘still to be (re)read’ pile).

Funny enough, reading the book it got clear to me very quickly that the author does NOT mean it ironically. He is actually looking for ‘true morality’. As the writer Iain King argues, in physics with Newton’s revolution (you know, the apple that fell on his head) we have found a certainty that is enticing. Since Newton we know the laws of gravity, of time and space (yes I know, my science heart already went into resistance here and I kept calling ‘what about Einstein?’ to the book). And that gives us certainty.

Philosophy, and certainly moral philosophy, needed such a Newtonian revolution, King states. To make this clear, he starts the book with three rather classical moral dilemmas. I will describe one here:

Sven lives in a dictatorship. It is a cruel regime that is kept alive by the notoriously ruthless police. He is offered a job with this police force. Sven hates the regime, but he knows that if he doesn’t take the job, Erik will get the job. Erik is a person who enjoys doing nasty things. Should Sven take the job and help to keep the cruel regime alive? Or should he let Erik take the job, knowing that Erik will work very hard for this police and that Erik will make the police even more ruthless?

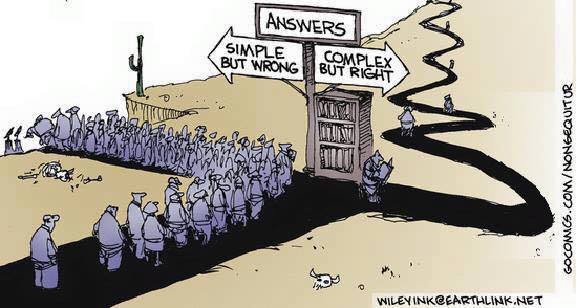

To establish that there is a correct answer to this dilemma, King spends 230 pages on systematically positing and ‘proving’ a universal moral theory. I put the word proving between quotation marks, because yes, I was not convinced. When King uses Sherlock Holmes to prove moral theories, I become a bit uncomfortable (‘it’s an imaginary person King!’). If the author ‘proves’ that the purpose of life is to generate value, by stating that the argumentation does not take into account the possibility that life has no (or no clearly formulated) purpose at all, but that in that case the whole reasoning is meaningless, so that that part may just as well be left out of consideration, I become desperate. The book is full of circular reasoning, post hoc propter hoc theorems and more nonsensical maxims. With King, ‘Proof’ becomes more like ‘throwing theses at people until they are numb’. I was not convinced (as you notice).

Anyway, I thought to myself: do you know, no matter how he comes up with it, maybe I’m too strict. Maybe I read it as a scientific book from which all notes and references have accidentally disappeared. Maybe I should read it more like a practical self-help book. Let’s see what he comes up with, maybe I can still use his guidelines on how to make good decisions.

King ends with 20 guidelines for making good decisions. In itself, most of them don’t even sound that bad. For example: ‘Have empathy, and be faithful to your obligations’, or ‘Help others with humility and be grateful for the help you get’. All fairly standard moral texts, which you also encounter historically in self-help books and religious texts. Some others, however, make me slightly uneasy: ‘Communicate in such a way that people act in a way that is optimal for the real circumstances’ for example. Or ‘Let people choose for themselves, unless you know their interests better than themselves’.

But the ‘proof of the pudding’ comes when we are back at Sven. Because King ultimately has an answer for this man in this rather dramatic dilemma. Now we know,’ writes King, ‘that Sven SHOULD take the job. It would be selfish vanity to refuse to dirty his hands. And while he does something only to prevent other people from doing even worse things, he must keep his bigger goal in mind: to overthrow the cruel regime’.

King continues with an even more astonishing sentence than previous advice: “What is special about this advice is that it is more than advice. This is the Right Answer (capital letters by the writer). It is not a matter of opinion, it is the truth.

Wow…. When I read this, I fell silent for a moment. I entertained the idea to throw the book out of the window. And then I realized: this book is for me the best proof of the necessity of my research. People who don’t look for doubt, for not knowing, end up always (or at least very often) falling into this kind of trap. A reasoning that seems logical at the beginning, if you follow it rigidly and monomaniacally, almost always leads to a nonsensical, excessive or at least questionable outcome. There is no truth. In spite of capital letters…

This book stays on my pile. Probably at a place of honour. Because for me it marks an important point in my research. Yesterday – I had just finished the book – I had my first consultation with a colleague to convert everything we know about doubt, changing our opinion, not knowing, moral truths and the influence of your emotional elephant, into training. A training in being ‘comfortable not knowing’. A training in the fact that ‘interdisciplinary working requires interdisciplinary looking’. A dialogue training for secondary schools, replacing the current debate training. And we have at least 10 other ideas.

Incidentally, yesterday we promised ourselves that if someone does not agree with our ideas for training, or wants to change our mind in any way, we should always take the space to say: Oh really? How interesting! Tell us your idea! Not knowing is in the end mostly practise what you preach. Building a training that is based on that starting point, may be a challenge 😉 But that’s what we are aiming for!