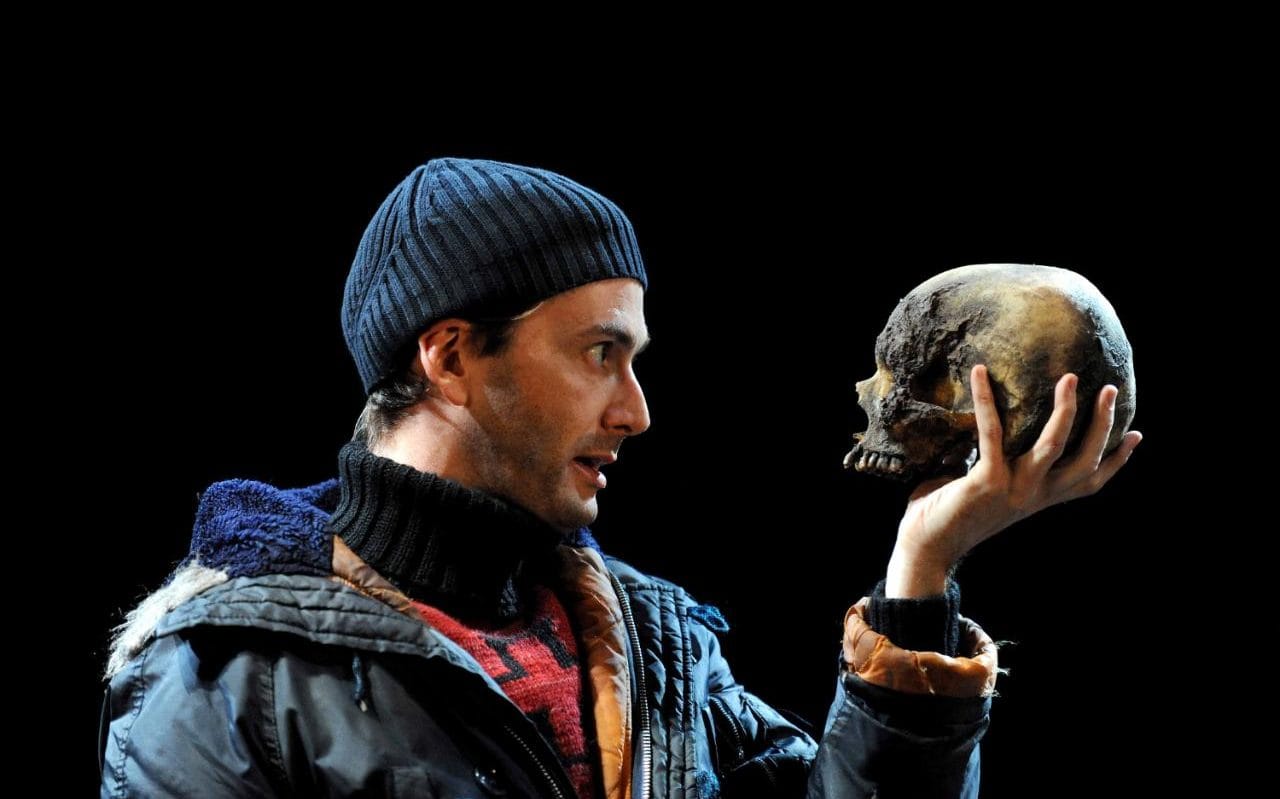

It was the first piece of prose I really learned by heart. Because of the beautiful words, whose meaning was lost to me. It just sounded so terribly beautiful:

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing, end them.

Hamlet is in doubt here. Should he live on, or commit suicide? He doubts very rationally: in a long monologue, he systematically weighs the pros and cons of death. I love Hamlet. I love his doubt, his willingness (whether or not of his own free will) to always look at things from several angles. Am I avenging my father, who wasn’t a kind man either? Is murder a good answer to murder? This doubt makes Hamlet a special ‘hero’. He is not (well, sometimes he is but usually not) a man of impulsive action. He’s not a superhero, he’s just a prince who doesn’t know what to do.

The contrast between reason and emotion, between ‘impulsive action’ and ‘quiet contemplation’ indicates how we think about emotions and reason. Our emotions add colour to life. Early philosophers like John Stuart Mill stated that pleasure is our highest attainable good. Maximizing pleasure is, according to Mill, a good basic rule for setting up a society. Since Mill we have gone of this rule a bit: the whole Enlightenment can be seen as an attempt by philosophers and scientists to impose reason and thinking as the foundations of society. As Descartes says: Cogita ergo Sum: I think therefore I exist.

The contest between emotion and reason is far from settled these days. Certainly not now that neurologists and psychologists like Joshua Greene and Jonathan Haidt are increasingly questioning the distinction between emotion and reason. Emotion can be seen as another form of thinking (see also previous blog). The difference between emotion and reason is not – they say – in the place in your body where it is made, but in the speed with which it works and the energy it costs to produce. Emotion is fast and cheap, thinking is slow and expensive. Emotions are our automated thinking patterns. They are thinking, just as much as reason is. But they are automatic, fast and therefore inflexible. And for that reason the should keep away from our emotional reactions, some people say. After all: they are not controllable! I feel before I know I feel.

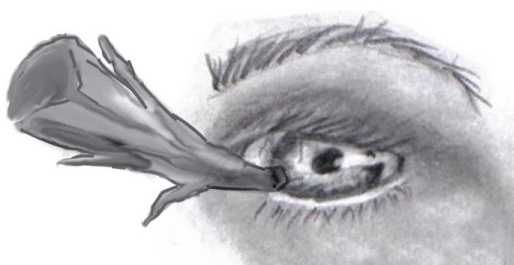

How to deal with such fast and inflexible patterns in our heads? According to Joshua Greene (Moral tribes), we have to go beyond the automatic setting if we want to bridge the problems of today’s society. We must see and use our emotions, but not sail blindly on them. We must disrupt our automatic setting. We must challenge and question our own built-in patterns. We can’t do that ourselves, because our emotions get in our way. But happily for us, we are not alone. So they call for a ‘community roast’: we must move towards a society in which we criticize each other’s ideas. Because while we may not be good at recognizing ‘the beam in our own eye’, we are all perfectly capable of seeing and naming ‘the splinter in the eye of the other’.

I have to say, I honestly don’t know yet. I have enjoyed reading the book by Greene and am delighted that he doesn’t just provide an analysis of how difficult it is, but also presents an action plan to make it better. But at the same time: how do I ‘roast’ my deepest convictions? How do I find a safe space, especially within myself, to question my truth? Who can do that? Who can’t? Before I offer up my deepest convictions for dissecting, I still have a long way to go.

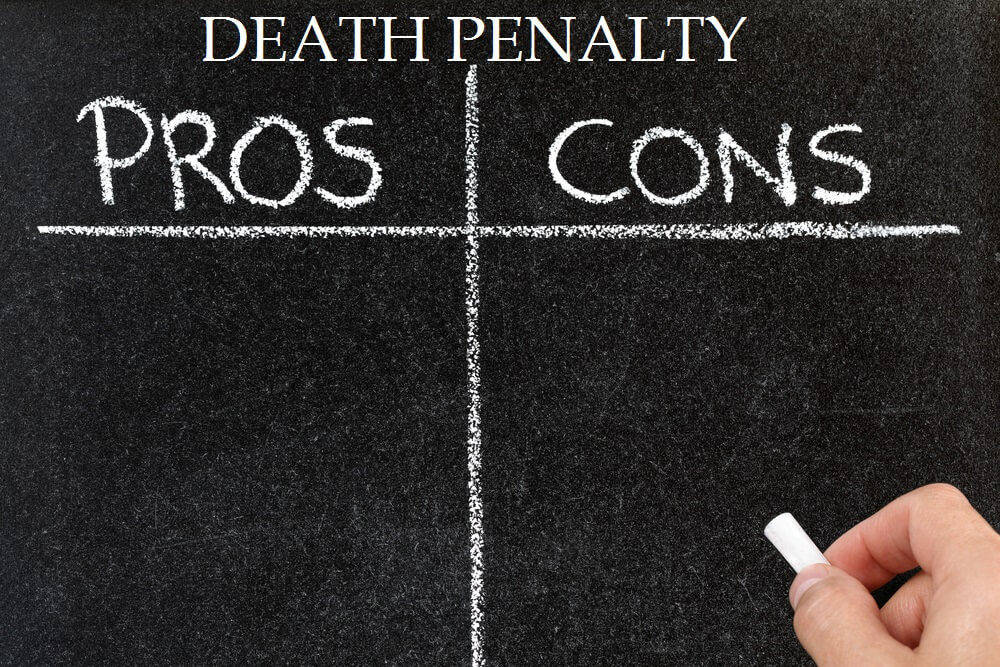

An example to make this clear. I am against the death penalty. I feel strongly about this point of view, this conviction. I can tell you a very rational story about why I have the point of view. Something with type 1 and type 2 errors and so on. It is a beautiful, scientifically sounding and rational story. Unfortunately it is also total nonsense. Because even if you could overturn all my arguments in a good conversation, I would say to you: I still think killing another person is just wrong. This is an emotional reaction, an automatic resistance in my body to harming others. Even if I know that this automatic setting tries to keep me away from a reasonable conversation on the subject of capital punishment, that doesn’t help: my body is locked into the emotion ‘this is wrong’.

According to Greene, there are methods to overcome this emotional reaction. Facts, science, curiosity and the acceptance of doubt are important. I hope he is right. At the same time I doubt if it is true (or at least my emotions do this doubting). And for that reason next week I’m going to try to argue why we shouldn’t try to overrule our emotions at all, because they are our best advisor 🙂