Sometimes things coincide in an almost magical way. Serendipity is the word: happy coincidence. Last week I wrote one of my most serious and self-critical blogs ever. I described how I systematically marginalize groups in my own society. How I don’t hear what they have to say and don’t take their viewpoint seriously.

A bleak discovery, also because I did not have an easy solution for the problem I saw. There doesn’t seem to be a magical wand that would suddenly let me look passed my confirmation bias. Was I doomed to keep my blinkers on, not ever getting beyond a hard won peak beyond the edge of the blinkers? Are we really trapped by our own prejudices?

Fortunately, I then read an article by the Correspondent (sorry, in Dutch) about silver foxes. And I read a book about Darwin and psychology. And together they managed to get me back on track. I would like to take you with me on my way back to a positive and hopeful future.

First the silver foxes. The article of the Correspondent actually starts quite negative. They wonder why it is that man has become the boss on earth. The Neanderthalers are stronger. Yet the Neanderthaler is now extinct in the museum, while we inhabit the world. How is that possible?

Theories about this soon take on a dark tinge. From the homo economicus to Locke’s philosophies: men are often portrayed as a race that is individualistic and in search of maximizing their own happiness. Nice when they have to be, mean when they can get away with it.

And then came those foxes. A scientist had done an experiment deep in Siberia: from generation to generation he had only bred with the least aggressive fox (it is a very aggressive breed). Nothing else was selected but friendliness.

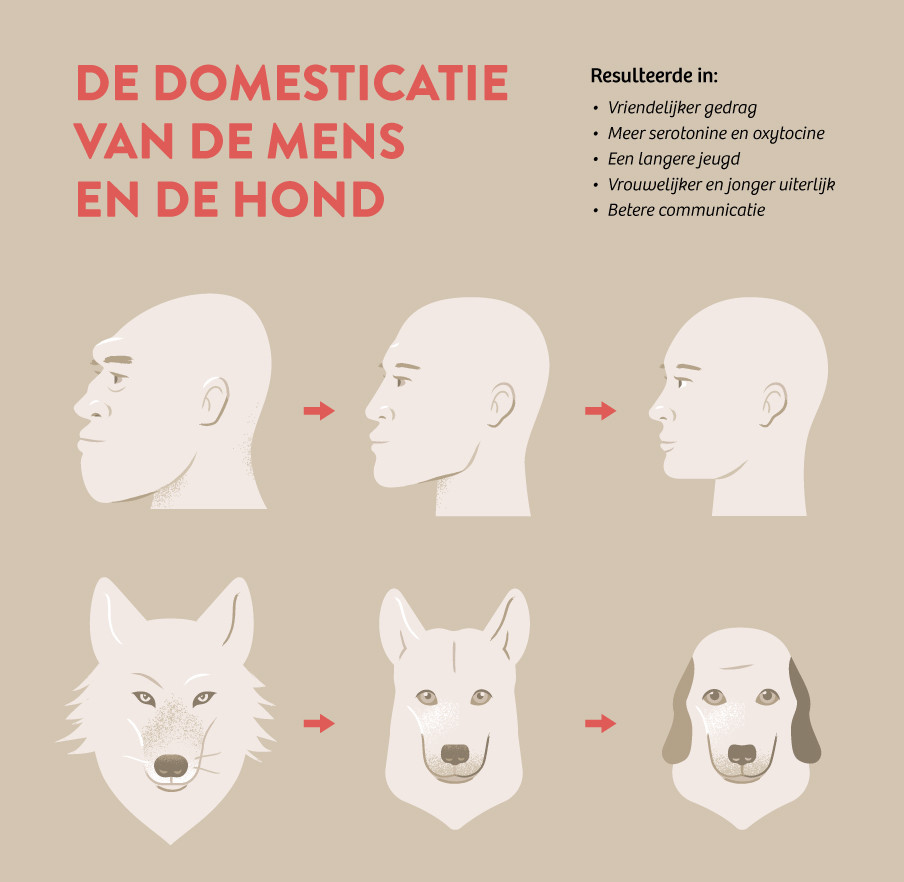

The effect of the breeding program was far-reaching: the foxes that were bred for friendliness also changed in other areas. The foxes became more childlike, more playful. Their fur got spots. Their brains shrunk, their jaws became smaller. In short, they started to look more like puppies. It looked like the domestication of the wolf to the dog. And perhaps also, the scientists said, on the evolution of man?

The theory is that people have also been breeding for friendliness for a long time. And that we have become ‘homo puppy’ in this way. When you see the pictures, you immediately believe it: our faces are much less pronounced (jaw line smaller, eyebrows smaller) and our brain pan has shrunk. To quote the Correspondent: “People became weaker, more vulnerable and more childish. We got a smaller brain, while our world became more and more complicated. Why? And how can this be an advantage?

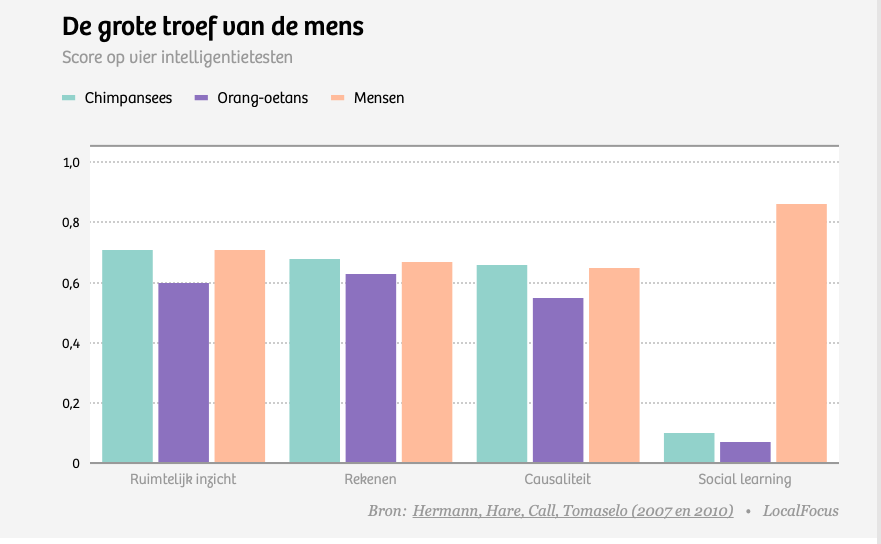

The advantage lies in our ability to learn socially. To learn from others. Social intelligence is what distinguishes toddlers in today’s experiments from chimpanzees. Our ability to share, to receive and to work in a group makes us more effective and, evolutionarily speaking, has probably caused our dominance on this earth. Friendliness is probably man’s greatest strength.

This realization made me happy. The book ‘The Righteous Mind’ by Jonathan Haidt helped me even further out of my winter dip. Not that this book is so very positive. The book tells about three important discoveries in the field of morality:

- Intuition comes first, rationality comes after that.

- Morality is more than honesty and care.

- We are 90 percent Chimpanzee and 10 percent Bij.

His first point boils down to the fact that according to Haidt, human reason cannot be pictured as a driver of a carriage (where the carriage is our emotion and intuition), but better a rider on an elephant. The elephant (our intuition) is so big, that it can only be adjusted marginally by the rider. The rider can try to steer, but will usually have to make due with a plausible reason why he wanted to go to where the elephant was walking anyway. In other words: in 95% of the time we do not reason to find truth, but to justify our actions.

Not very positive of course, but insightful. It became a positive thing for me when Haidt told me how to deal with my elephant. The intuitive reaction to things around you cannot be switched off. But this reaction is not only superfast (and therefore always earlier than reason), it is also fleeting. Subjects who had to wait 2 minutes to answer moral questions, answer more clearly and rationally (not triggered by the elephant) than subjects who had to answer immediately. Tranquility, time, attention: it can help to guide your elephant. It feels a bit like anger or sadness: pushing the elephant away can lead to enormous problems and is usually not as efficient, but letting it rage for a while, can give room for a more balanced conversation.

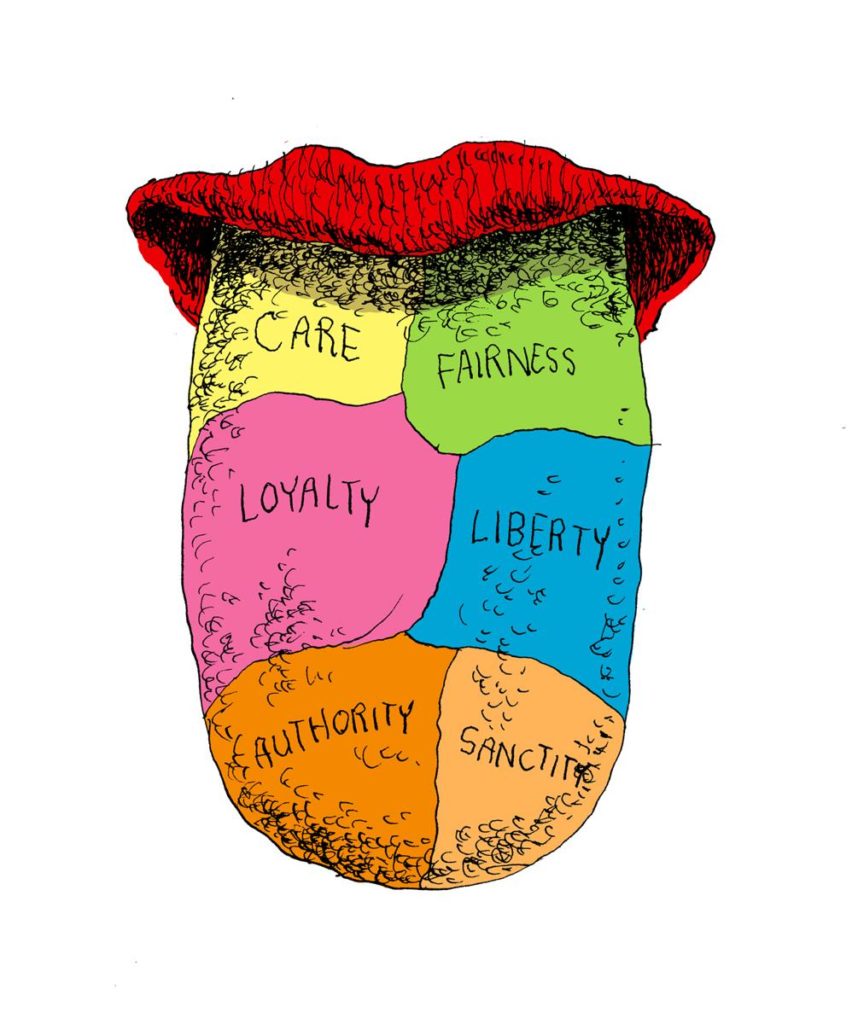

His second point is why we disagree about what is morally good. There are, says Haidt, several parts of morality. And although these parts are limited (he comes to six ‘tastes’: Care, Liberty, Fairness, Loyalty, Authority and Sacredness), the combinations that can be made with them are infinite. As a result, groups may start from the same base set of norms and values, but because they consider different parts to be the most important, they may arrive at a different moral assessment. Understanding this consideration, says Haidt, cannot be done without immersing oneself in all six parts of morality. A plea for more insight and curiosity about the other person’s truth.

Finally, Haidt discusses the eternal opposition between psychologists and sociologists: is it about the individual or the group? Haidt states that both are at essential parts of understanding morality, and that we should not skip group dynamics when trying to understand it. Group processes such as raves, religion and the Sunday football game make us more resilient, efficient and – for the others within our group at least – nice. Group processes can also have very nasty effects, especially for those we do not count as part of our group. But the solution that every person should belong to everything, John Lennon’s vision of the future in the song ‘Imagine‘, could be very negative according to Haidt. We need – he says – belonging to a group. If only because in that group we can really use the advantage we have as ‘Homo Puppy’. The Homo Puppy thrives best in a pack.

What did the book and article teach me? That I can expand my blinkers. I want and will dive into that moral plurality. From my background and environment I am much more familiar with the parts Honesty, Care and Freedom of morality. Loyalty is kind of neutral to me, Holiness is a large white space in my mind and Authority even evokes negative associations with me. I want to feel and notice how these parts are of value to other people, how they can have a positive contribution to the moral compass of a society.

The images of the Homo Puppy, who excels in learning from others, and of the rider with the elephant, who has an immediate but fleeting first reaction, will also stay with me. The Homo Puppy gives me the confidence that we can move forward together. That setting a good example really makes it easy to follow. Something we also see in today’s society. It’s not only torment and sorrow, tribalism and polarisation. There is also a Gilette advertisement (see link below), which shows how men can be a better role model for their sons.

And my elephant? From now on I will give them more attention and space just to be present. Without behaving like an unwilling follower of his preferences. He may make the first move, but if I, as his rider, will take the time to have the last laugh.

You really got me in this one. Thank you for being diligent to study the seemingly impossible social trends. What is good and of value varies daily as I react to changes around me. I isolate to the studio so I don’t have to cringe at my clumsiness- misunderstandings happen rapidly, so I hide. You really gave me a new way to see through this. Really. “I want and will dive into that moral plurality. From my background and environment I am much more familiar with the parts Honesty, Care and Freedom of morality. Loyalty is kind of neutral to me, Holiness is a large white space in my mind and Authority even evokes negative associations with me. I want to feel and notice how these parts are of value to other people, how they can have a positive contribution to the moral compass of a society.” Bravo. Your studies bring wisdom.