I was entering in a pub quiz on Saturday evening. Nice, especially because I was a popular team member. That was mainly because I was one of the few people there over 40, but we will ignore that fact for now. There were eight rounds of questions, we became second (yes, that was all right) and we had a lot of beer and a lot of fun.

Sometime during evening, the conversation turned to philosophy. One of my team members was following Harvard’s ‘Justice‘ course, after my enthusiastic recommendation. He enjoyed the lectures, thought the material was interesting, but one thing bothered him: it was of little practical use. I asked why he felt that way and he explained: “Philosophy is so vague. I’m a lawyer and in that profession, the rules are clear. But with all those philosophy lectures the conclusion is: you can look at it like this, but you can also look at it like that. I always wonder, how can I use that knowledge in real life?

This conversation gives a nice indication of how I am currently feeling in my research. Incredibly instructive, enlightening and interesting. I enjoy, struggle and learn… But I am also disturbed by the same points as my fellow student: what can I DO with al the knowledge I’m learning?

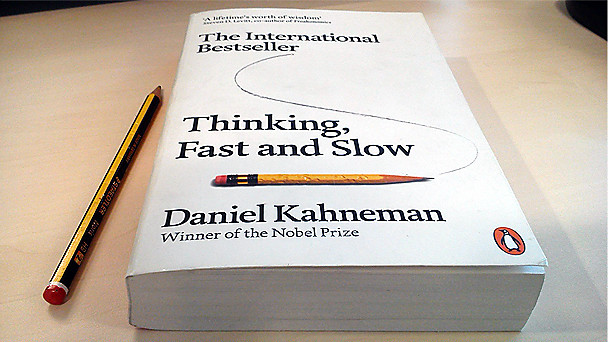

From Think 101, the incredibly interesting lecture series from the University of Queensland, to my last book, Being Wrong by Katheryn Schulz: over and over again it is explained and described how the process works in your head and body. And again and again I’m left with a ‘yes and what now?’ feeling. As Daniel Kahneman said in Think 101 (to my great frustration), when asked how you can change how you think: “Choose one aspect that really annoys you, and work hard and consistently on it. Maybe you’ll see a small change then. Don’t expect too much, because I’ve been studying how to think better for more than 20 years, and my thinking hasn’t improved significantly.”

In the studies I did after Think 101, I kept reading the fact how incredibly complex it is to intervene in the system that forms your opinions and worldviews. Not only is it difficult to specify where you should intervene (after all, opinion-forming takes place in a complex dance between intuition, emotion and mind), it is also a largely unconscious and super-fast process. We are simply too late with our interventions, by the time we think of them.

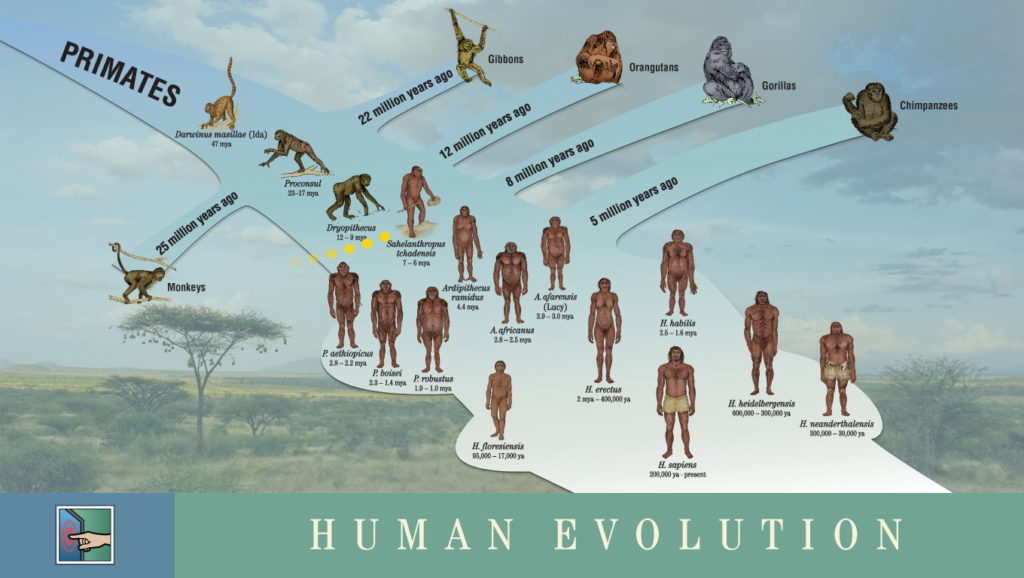

My findings are a little more hopeful when I don’t focus only on what is happening inside me. Evolution theory teaches me how important our environment, our groups are to men. And it teaches me we excel in using this group strength to work together and to learn from each other. Group processes bind and blind, as Jonathan Haidt says. It is not automatically a positive influence, this group influence. But at least my research shows me that behavior, opinion and world view may be easier to influence outside of my head than inside it.

So, it’s time for a ‘come on Marian, don’t overcomplicate everything’ summary of my research so far. With a focus on the happy, nice, positive things. On concrete points that I can really do something about. Here are my ten concrete ‘yes, I can do something with this’ points:

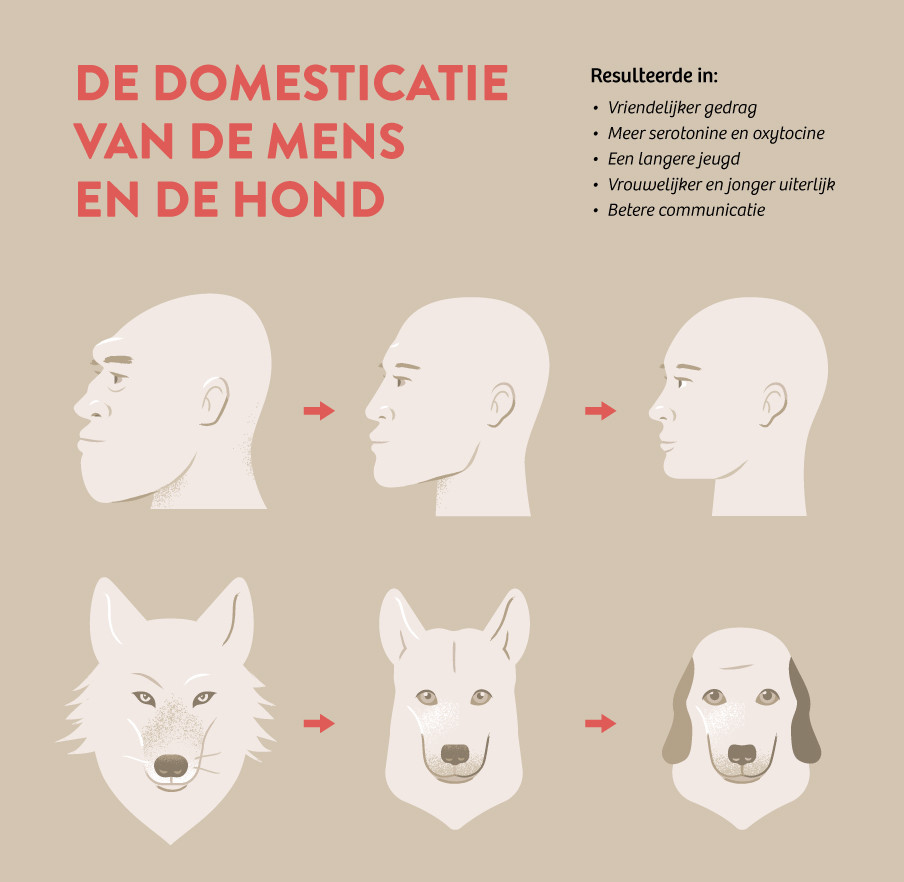

- We are Homo Puppy. We have genetically evolved specifically to be less soloistic and to rely more on each other. As a result, we can learn very well by imitating others.

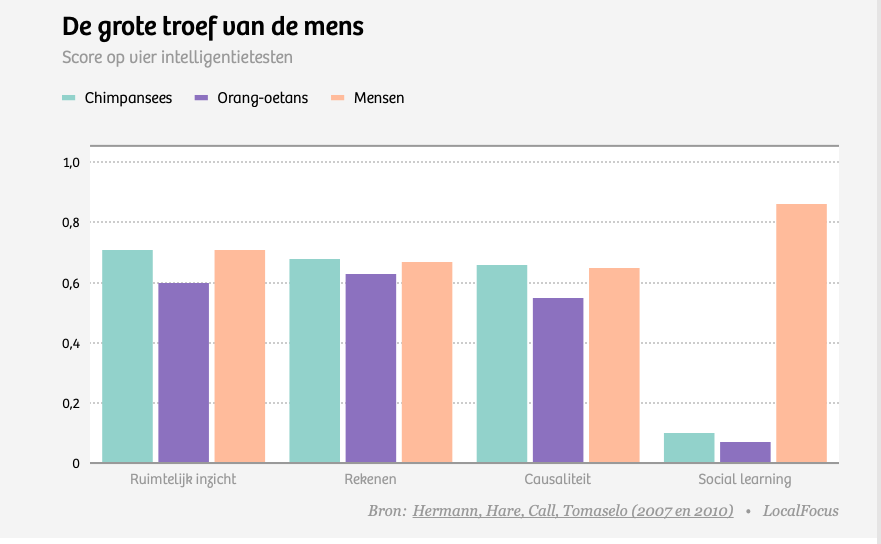

- From an evolutionary point of view, we can also conclude that man has come where he is, through division of labour (and thus interdependencies), the sharing of our food (needed by the division of labour) and through stories (we were eating together anyway).

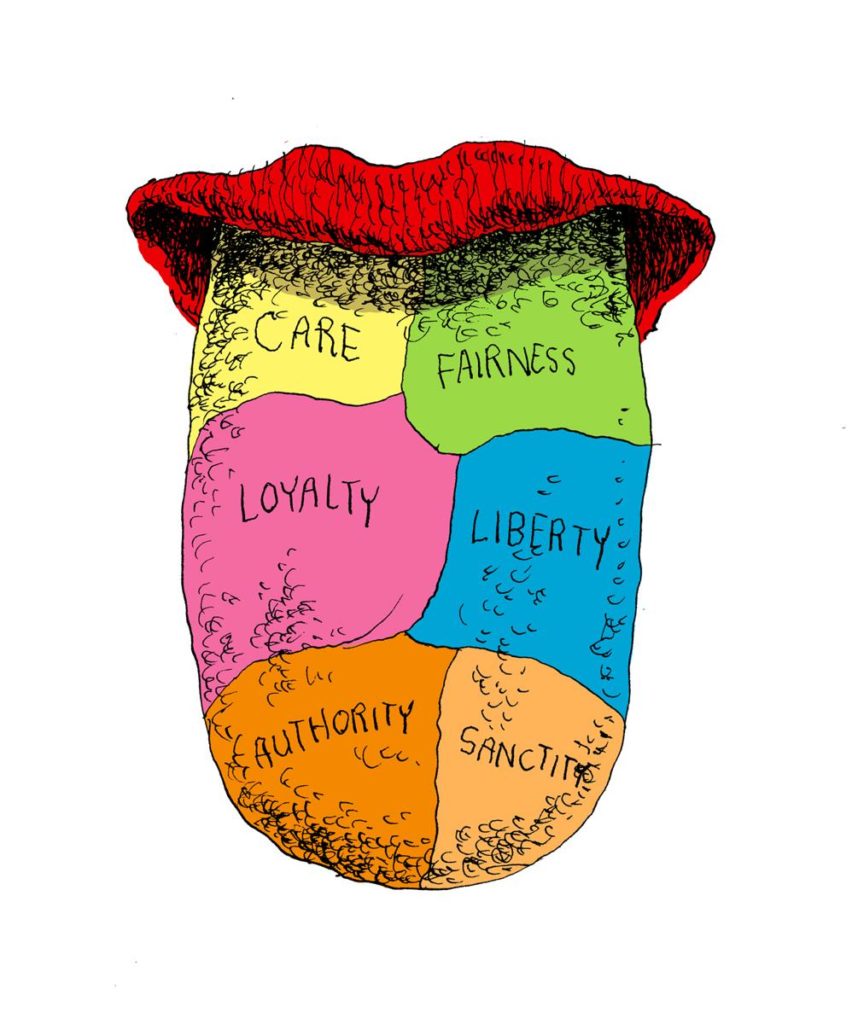

- Our moralities are not black and white, or excluding each other. All moralities around the globe are built up around six specific elements. The great thing about this is that we have a shared language when it comes to our values and norms. The differences between groups are mainly due to the priorities we set, which element(s) we value most.

- Stories matter (see point 2). If we can hear, feel, tell each other’s stories, we can really be in dialogue. Stories about the morality of the other, written from within, make our worldview more complete and colourful.

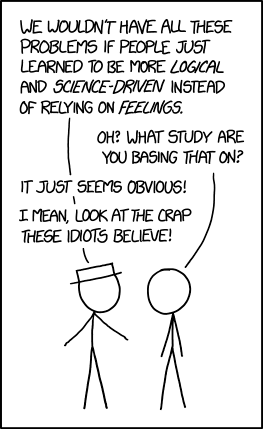

- We limit ourselves with help from the confirmation bias and the Dunning-Kruger effect: we only see facts that confirm our worldview, and we think we know more than we actually know. This results in an inability to look at ourselves. This inability is almost impossible to overcome. But: we can look at another person! Working together seems to offer opportunities to escape the built in pathways in our brain.

- We think that we think, but secretly we mostly feel. Emotion and intuition have a much greater influence on our opinion than we realise. Just think back to that research that showed that people judged moral dilemmas much more strictly when they smell fartspray. Emotion and intuition is lightning fast and inevitable. But, it is also fleeting. Giving yourself time, letting the emotion go before you form an opinion, is a very effective way to let yourself be influenced less by your unconsciousness.

- We do not reason to seek the truth, but to convince the world we are right. This is a hard truth, but an instructive one. So every argument I think of has the ‘secret’ purpose of overturning an argument of ‘the other’. It is instructive, useful and incredibly headache-causing to look at your own arguments in this way. With every argument of your own, can you find the argument from the other perspective?

- Openness helps the process. Making mistakes, changing opinions, being wrong: the shame that comes with it in our society is the biggest reason for the festering effect. Making mistakes and being wrong can also be light-hearted and easy. Transparency and a culture in which making mistakes is not directly linked to being inferior helps to make your head and heart more flexible.

- Laughter and fun help enormously. The main reason why doubt, making mistakes and being wrong feel so negative is because we take it so seriously. Just look at your favorite comedy shows: making mistakes and being wrong is often an important part of the humor. Or look at children, who fearlessly look for new ways to make mistakes.

- It is impossible to take the previous nine lessons into my daily life in their entirety. But I can play with it, practice it. Reading an article from two different moral viewpoints. Recognising the elephant (your emotional and intuitive reaction) in yourself and others. Constructing the other person’s story: if I work on it, take time for it, then I (sometimes) succeed. And when I succeed, it enriches my life.

This list is probably not complete, and certainly not completely scientifically proven. But still, it works for me: Ten lessons to get started. Ten viewpoints that help to make my world more beautiful. Ten ways to change my mind in the 21st century.

Post Scriptum

An anecdote to end the tale. Yesterday my son had to do some homework. He had to come up with arguments for or against the following statement: All teachers have to take an IQ test. He could choose whether he was for or against this statement.

Choosing was difficult, but after a lot of doubt he chose to come up with arguments against the proposition. Five minutes and three beautiful arguments later, I challenged him to come up with two or three arguments in favour of the proposition.

And although it was only five minutes before that he could hardly choose whether he was for or against the proposition, it was no longer possible for him to come up with good (not cynical or ridiculous) arguments in favor of the statement. He even yelled at me irritatedly: I can’t do that mum, because I’m too much against this!

That is how fast our mind works…… And yes, there is something we can do about it! Brain gymnastics every morning, but not to remember better or to become smarter, but to stay flexible in your mind. As the Queen of the Heart in Alice in Wonderland spoke: