My quest has started. Now that I have discovered that changing opinion is indeed very difficult (see Through the Looking Glass), I’m delving into the reason why this is so. This week: social media, primates and brains.

First, I dive into social media. I read the book ‘Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now‘ by Jaron Lanier. The book paints me a gloomy picture: Social media hs nothing to do with connecting people. It has to do with growth, data and making money.

Lanier gives ten reasons why you should delete your accounts. In fact, all of these reasons are based on the ‘Bummer-machine’ he describes, which runs under the hood of many social media. The Bummer machine can be divided into six elements:

A is for Attention acquisition.

B is for Butting into everyone’s lives.

C is for Cramming content down your throat.

D is for Directing behaviours in the sneakiest way possible.

E stands for Economic gain.

F stands for Fake groups and fake society.

In this machine, part E is the force that drives all other elements. As Lanier describes: economic gain is the goal of the companies behind the social media. And economic gain can be maximized at the least cost through Attention, Butting in, Cramming, Directing and Fake. I won’t go in to all his arguments here (read the book!) but the picture he paints is depressing. Social media aren’t intentionally ‘bad’, but the economic model in which attention and data have become money, leads to very perverse effects.

In an article about Facebook in The New Yorker, this Bummer machine is explained further. A former Facebook employee talks about Facebook’s most important ‘target’, the L6/7 (how many people log into Facebook six out of seven days): “You could say it measured how many people love this service so much they use it six out of seven days. But, if your job is to get that number up, at some point you run out of good, purely positive ways. You start thinking about ‘Well, what are the dark patterns that I can use to get people to log back in?“

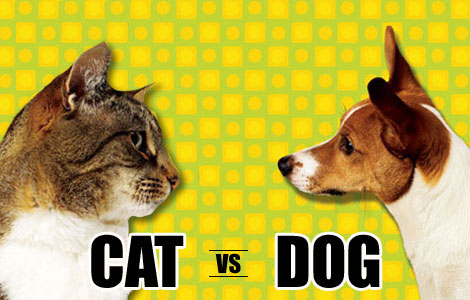

Lanier’s solution is simple: be a cat. Don’t walk like a dog in the pack and don’t look for approval, but follow your own path as a headstrong cat-like. And follow that path without using social media. Not because there is no internet – or social media – possible without exploitation, but because at the moment almost all large companies still choose to take exploitation for granted as the shortest way to profit.

I read Lanier’s book, read the article in The New Yorker, and deleted my Facebook account. It felt like a relief. But at the same time it felt like it was ‘too easy’. What now? Did I have to wait for a ‘reliable’ social media to emerge? And who should I believe telling me that this next option would be better? Should I fulfill all my social media needs on Linkedin (a platform that Lanier says works without the Bummer machine)?

I still felt like a dog, only now I followed another pack. I wanted more, I wanted to choose for myself. And so, I decided, I had to delve into the why: why does the Bummer machine work? What’s embedded in my system, that I’m so easily tempted to get negative content pushed through my throat and that I want attention? What happens in my head, in my heart and in my abdomen? And above all: can I do something about it? Can I become a conscious consumer of social media?

To find out, I read a book and went on to follow two university courses. The book was ‘Factfulness’ by Hans Rosling, the courses are ‘Evolution of the Human Sociality: A Quest for the Origin of Our Social Behavior’ from the University of Kyoto, and ‘The science of everyday thinking’ from the University of Queensland, both via edX.

What the courses, but especially the book, have taught me, is that there are indeed certain things that are embedded in our heads. But not irreversibly. The ingrained patterns are more a consequence of unconscious thought processing. they are mostly logical ‘short cuts’ that are smart most of the times, but when used unconsciously can lead to faulty conclusions. In short: we use these short cuts in our heads to avoid having to think about everything, every time. That is very good and necessary. But the short cuts used, become so unconscious that we are no longer aware of them when we use them. And so things can feel ‘true’ and ‘well-considered’, while they are only a guess.

Fortunately, it is a positive and activating book, which not only indicates what goes wrong in our heads, but also how we can arm ourselves against it. The ten ‘rules of thumb’ for conscious consumption are:

1. Gap: look for the majority, not for the gap.

2. Negativity: count on bad news, because good news is less often told;

3. Straight line: lines can bend, be careful with extrapolation;

4. Fear: Calculate the risks;

5. Size: see things in proportion;

6. Generalization: question your categories;

7. Fate: slow change is still change;

8. One perspective: make sure you get a toolbox;

9. Scapegoat: don’t blame anyone;

10. Urgency: take small steps.

I’m not going to elaborate on all of these heuristics in this blog either, because it’s really too much fun to read this book (especially if you’ve become a bit depressed after John Lanier’s book and the article in The New Yorker). I’m guessing that I’ll come back on some of these in future blogs, because I think the heuristics and mechanisms Hans Rosling explains, really underlie a lot of the dillemma’s about changing your opinion.

For this blog it is enough to share that I have successfully applied the rules of thumb online. Especially on Twitter, where I get a lot of my news. The difference in how I experience reading my feed is really amazing. Knowing that certain messages – negative, anxious, urgent and giving me a scapegoat – enter my head as if they are boldly printed in capital letters, (UNSAFE NUCLEAR PLANT KEPT RUNNING BY GOVERNMENT!) helps me to put them into perspective. Knowing that my head is not good with numbers and is scared of large numbers (4.2 million babies died worldwide in 2017!), helps me to take the time to read on and understand the story behind these kind of figures, before I draw conclusions. The information I received in the book about the state of our world (a small hint, the world is doing better than you think) helps me to stay positive in an environment that is currently flooding me with Kavanaugh, Net Neutrality, Dividend Tax and the Childpardon (last two subjects are really Dutch).

With the help of Hans Rosling I start to feel more of a cat every day: independent and self-confident. So I confidently choose to use some social media still, despite their Bummer machine. Twitter remains a place where I find news and share my story. Instagram is where my adolescent son lives and where I want to keep living. I did delete my personal content there. I completely removed Facebook, with some heartache, because I used it to keep in touch with friends who live far away. And so I walk through the social digital landscape and make my own choices. Maybe not always the best ones, but at least more and more conscious choices.

Links from this story:

The title is a quote from episode 4 of the TV series: Lost in Austen

edX (where you can follow courses like I did and many other beautiful courses)

‘Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now.

Article New Yorker on Facebook and Mark Zuckerberg: Can Mark Zuckerberg fix Facebook before it breaks democracy?

Opinion New York Times on regulating social media: The slippery slope of regulating social media.

Article in the correspondent on how your brain works: Weet dat je te weinig weet (Dutch article).