Do you know those bar jokes? A rabbi and a pastor enter a bar? The result is always a form of confusion. And it is usually quite funny. In recent weeks more and more jokes have been gurgling around in my head that resemble those bar jokes. They are about Truth and Righteousness, and are usually just as full of confusion. But I can’t laugh at them. For Truth and Righteousness are for me pillars of my existence. I assume that I know what is true, and that I do the right thing. Beacons in my upbringing, roadsigns on the way to adulthood. Search for truth and act righteously. Laughing at Truth and Righteousness is therefore very difficult for me. And yet I increasingly discover that there are serious problems with these beacons from my youth. Next week I will find out what the situation is with Righteousness, today I will examine Truth.

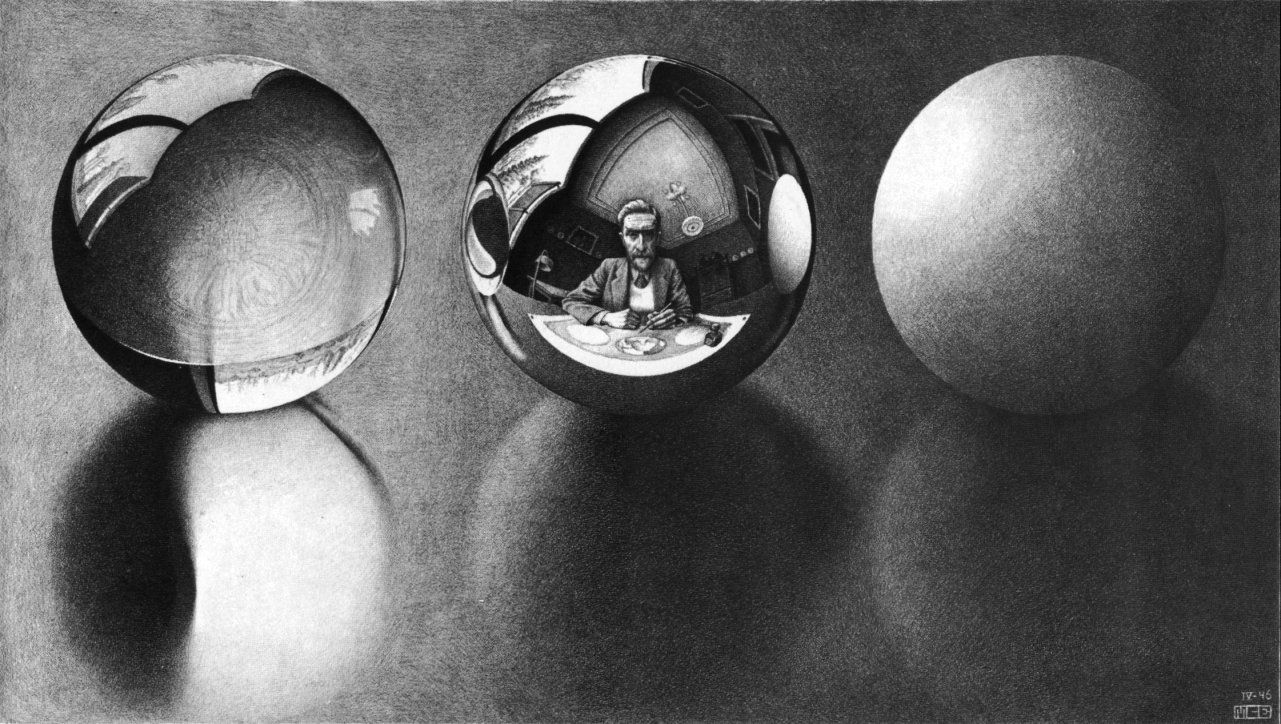

The first crack in the mirror of Truth came at university. I studied physics. We talked about electricity and magnetism, and about mass and speed. We did experiments and calculations and felt powerful. Until one of my teachers, in a lesson about light and reflection I believe, asked us if the table we were sitting at would be there if we didn’t look at it.

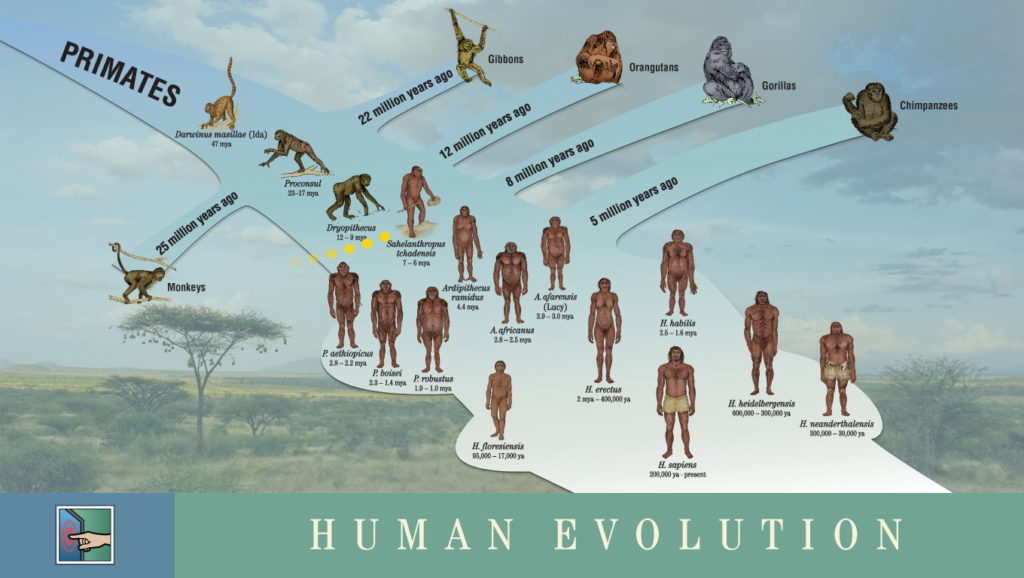

And no, it was not a philosophical discussion. The discussion was about light, about reflection, about proving that molecules (and the even smaller elements of molecules) exist. We obtain the technical proof for this through collisions. In Switzerland, at CERN, we collide particles at high speeds to see what there is. Nice technique. But, said the teacher: if you can only see something by colliding it with something else, then does it also exist without that collision?

I still don’t know if the table I’m typing at is there, when I’m not in my office. I hold on to the idea that everything just stays where I put it, even when I’m having lunch. That my world is real, and formed the way I see and touch it.

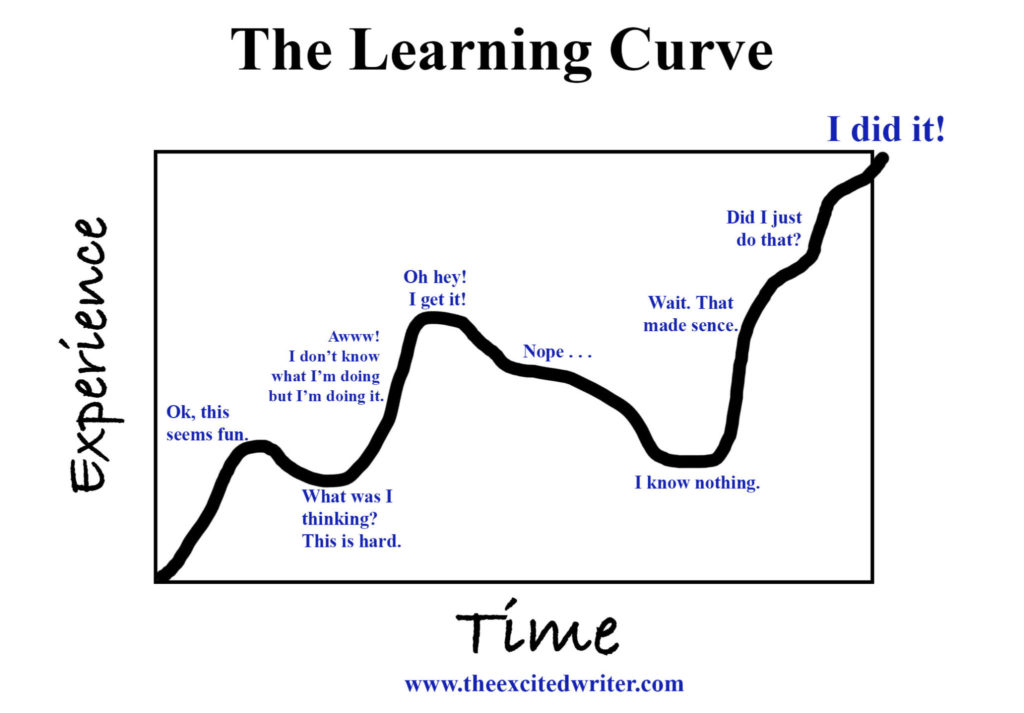

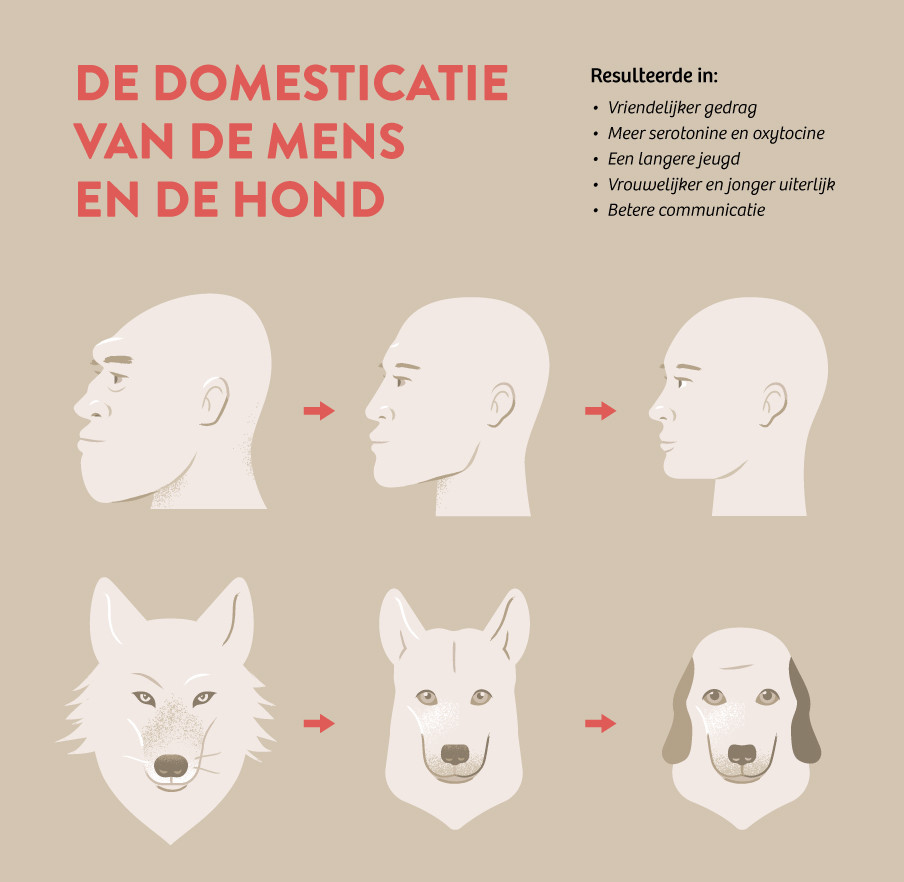

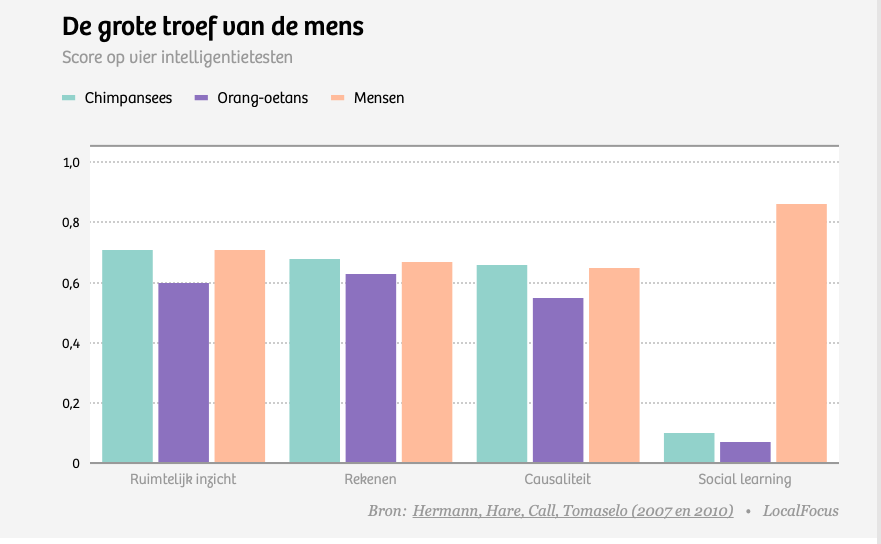

But when I walk outside with my dog, we both walk in a totally different world. Mine is full of colours and shapes, his is full of smells and sounds. Who is right? Which world is true? Scientists conclude that in our first years of life we are very busy understanding the input our eyes and ears give us. We make pictures in our heads that fit as well as possible with the input we see. But at some point our brain is ‘done’ with this, and the rest of your life you have to do with the interpretations you have collected up until then. A nice anecdote to illustrate this: I grew up in the centre of Haarlem, and when I was three, our family moved to a suburb with grass and pond. When I saw a duck in the pond by our new house, I called it a pigeon. And when we went to town for shopping, and my sister saw a pigeon, she called it a duck.

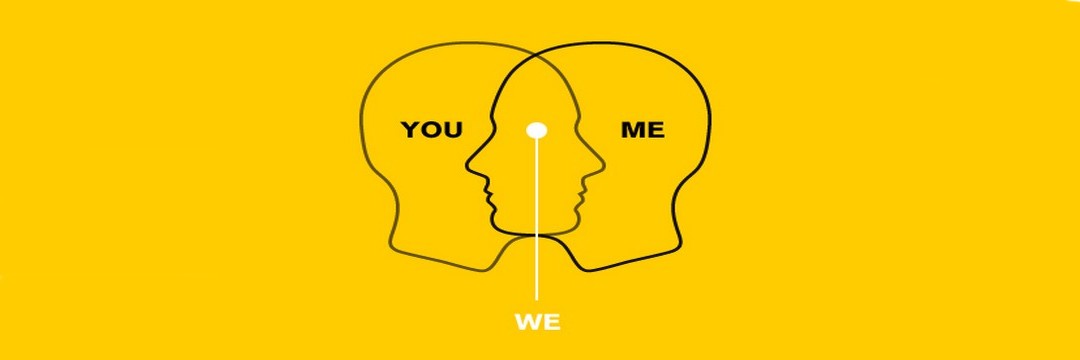

Truth, it seems, is something we build in our heads. We use the input the world gives us, but we interpret it. As Multatuli said: ‘Maybe nothing is entirely true, and not even that. Your eyes fool you, and once you have used your eyes, your brain does the rest. With all the shortcuts we have discussed earlier, such as confirmation bias and cognitive dissonance. We don’t see what we think we see, we construct a truth. And once we have built that truth, we then only see those things that confirm our truth.

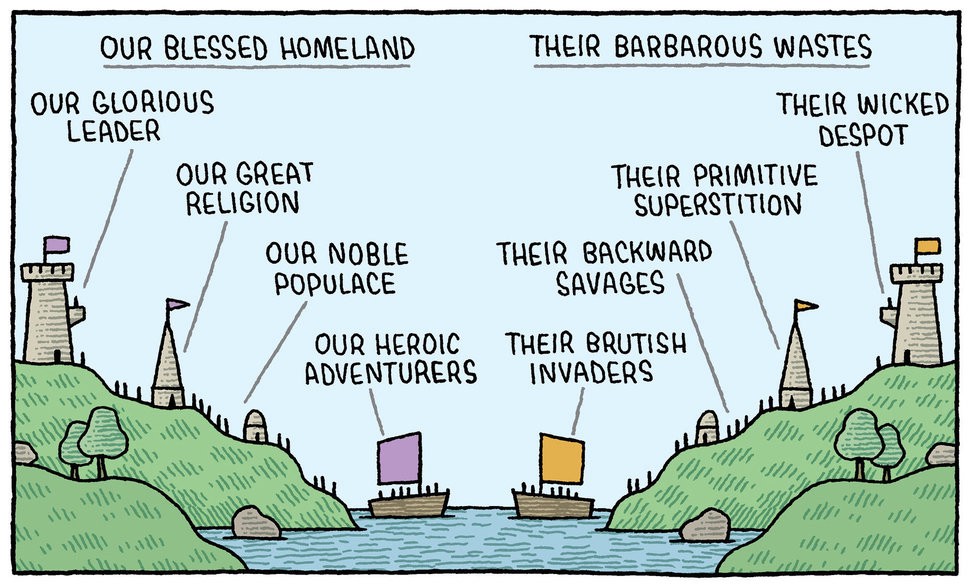

In Will Storr’s book ‘Heretics‘ the author describes many examples of our truth distortion. Renowned scientists who dismiss facts on semantic or detailist arguments because they disagree with the content of the facts. Two different people who look at the same object, but see something else. The most memorable (if horrible) example of this in the book is when the author is undercover on a journey with Holocaust deniers. They are in Auswitz at the gas chambers, and the tour guide shows that the door of this room has a handle on the inside. Prove – to him – that this room was not a real gas chamber. The author looks at the same door, and sees the locks on the outside of the door. They both look at the same door, but their eyes register different parts.

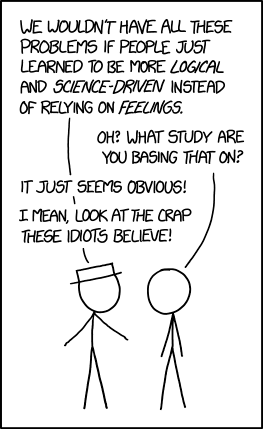

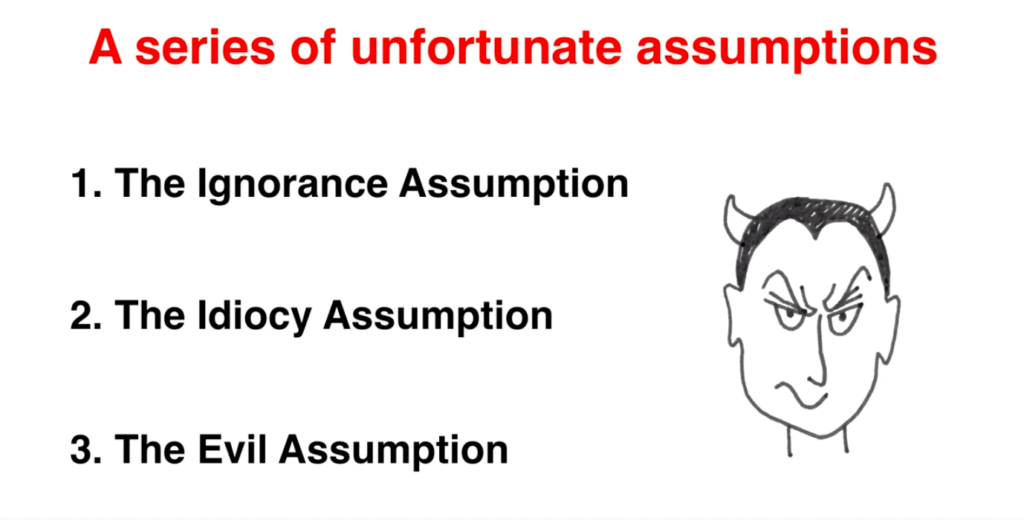

This piece from the book is horrible and chilling to read, especially because I don’t want to look into the head of a Holocaust denier. Such a person just has to be very badly informed, very stupid, or very evil (a quote form Kathryn Schulz in her TED talk about why we think other people are wrong). Storr shows me the possibility that the truth is more complex than I can accept in my heart.

Truth, it is an essential part of our society. And at the same time something totally elusive. As they write in this article about narrative journalism (sorry, in Dutch) at Follow The Money: the danger of telling stories that are meant to convey the truth, is that a story has to be completely true. There should be no contradictions, no white spaces. A story only runs smoothly when it takes you all the way, sucks you in. You don’t do that by constantly contradicting yourself. You do that by building up a compelling and storyline.

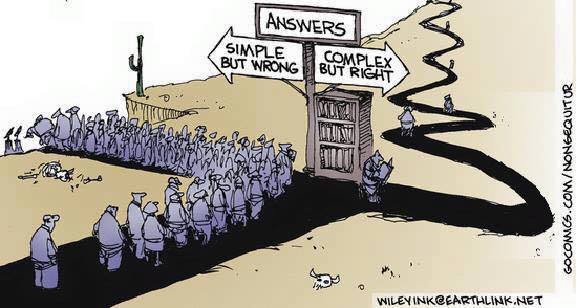

However counterintuitive, this is where I learn my most important lesson: beware of stories, of truths that are completely true. Beware of people who know for sure. The presence of contradictions, doubt and uncertainty in a story or in an opinion, is a good indication of his truth. Because real truth? It is always more complex than we think.